“Who Speaks for the Negro?”: Digital Archives, Split Collections, and Hearing the Fight for Civil Rights, an interview with Mona Frederick

In 2012 the Jean and Alexander Heard Library and the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities launched the “Who Speaks for the Negro? Digital Archive,” a collection of audio recordings and transcripts housed at the University of Kentucky and Yale University libraries. I first learned of the “Who Speaks” archive during my pro seminar when Mona Frederick, the executive director of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, came to give a presentation on the website and its creation. The digital archive is a curated repository of the interviews Robert Penn Warren recorded with key figures of the Civil Rights Movement, which would become the basis for the oral history component of his 1965 book Who Speaks for the Negro?

I had the pleasure of talking with Mona Frederick about the creation of the “Who Speaks” digital archive and the considerations the project team encountered while compiling audio recordings stored on reel-to-reel tapes held by multiple university libraries. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Nathan H. Dize: How did the idea for the archive and the website come about? What types of institutional partnerships had to be created to support the project?

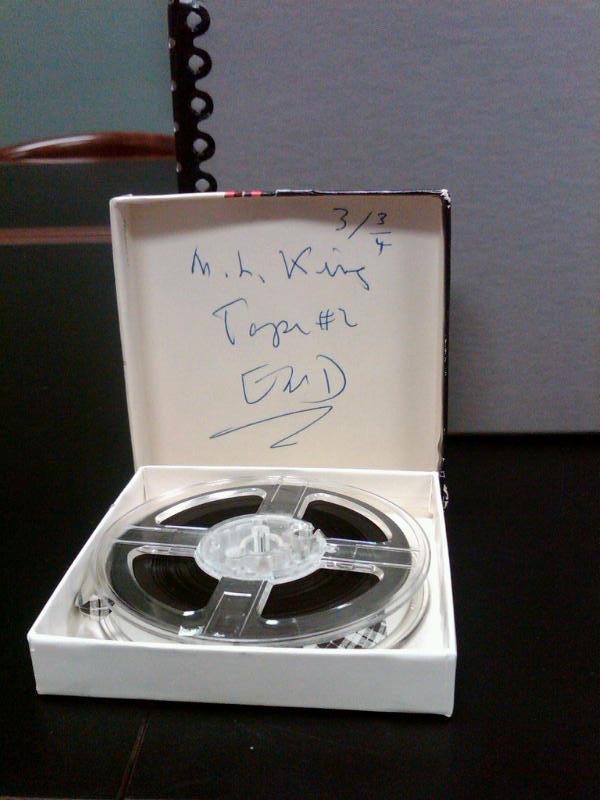

Mona Frederick: Sometime in 2006 or so, I was reading an article about the rich collections held at the Yale University Library and I noted a very brief mention of boxes at Yale’s Historical Sound Recordings in Sterling Memorial Library containing the old reel-to-reel audio tapes of Robert Penn Warren’s interviews with civil rights leaders conducted in preparation for his 1965 publication Who Speaks for the Negro? My jaw dropped as I thought to myself “These audio tapes still exist and are sitting in boxes at the Yale Library?” Immediately I knew that these valuable conversations must be digitized so that everyone in the world with access to the internet could listen to these important reflections about the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. Little did I know, of course, what a long journey this would become! The archive was completed in its final form in 2012.

The project required tremendous institutional support and many partners. First and foremost, I had to procure permissions from Warren’s family to digitize the audiotapes and other material related to the archive. His children, Rosanna Warren and Gabriel Warren, granted the permissions quickly. They were delighted to have these conversation made available to the general public. The Yale Library was extremely cooperative in working with us to achieve our goal to digitize the tapes and, later, the written materials related to the project.

Colleagues in the Jean and Alexander Heard Library created the first online archive made up of the digitized oral interviews in 2008. Special thanks go to Paul Gherman and Jody Combs for their leadership in supporting the creation of the initial digital archive. Librarians Jodie Gambill, Deborah Lilton, Dale Poulter, Suellen Stringer-Hye, and Pete Wilson were also critical members of our team.

After the creation of the initial online archive, I discovered that the collection of Warren’s audio tapes had somehow been split, and tapes I thought were missing were actually held by the University of Kentucky Library. Librarians at the University of Kentucky were supportive of our project and the archive was enhanced with their support.

I continued to hope that I could expand the archive to include photographs and written materials such as transcripts, book reviews, letters, and the like. But this was a very expensive undertaking. At a critical point in the life of my project, an anonymous donor stepped forward to provide needed financial support to allow the digital archive to expand into its current form. At Vanderbilt, the Office of the Provost and the College of Arts and Science Dean’s Office also granted key fiscal backing.

The Vanderbilt University Library has been supportive of the project throughout the development of the expanded archive and my work has benefited tremendously from their guidance and expertise. The “Who Speaks for the Negro? Digital Archive” is a marvelous example of how split collections can be made whole, and how outdated technologies such as reel-to-reel tapes can be digitized to allow broad general access to the materials. It is also a shining example of collaborative work between three university libraries.

NHD: I get the sense that this archive is more than just a documentary history of the fight for civil rights in the US South from the perspective of influential actors, could you characterize the collection a bit? How would you describe it?

MF: The archive is fascinating on many levels. At the time that Warren was conducting and recording his interviews, the field of oral history had not yet been codified—the Oral History Association was formed in 1966—so he can be seen as an early practitioner in this area. Tape recorders were somewhat novel instruments and, in the interviews, you will often hear discussion about the tape recorder itself.

I also think it is noteworthy that Warren’s interviewees were not exclusively in the south. One recording is titled “Bridgeport, Connecticut Men.” His interview with Malcom X takes place in Harlem. He travelled to Cleveland to interview several activists there. I think it matters that he recognized that the fight for Civil Rights was occurring across the country, not just in the southern United States. Furthermore, he interviews well known figures—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell—as well as people who were young and/or unknown outside their immediate areas—Clarie Collins Harvey, Joe Carter, and a group of Tougaloo college students. The fact that he included women in his list of interviewees is also somewhat remarkable given that the role of women in the Civil Rights Movement was rendered almost invisible at the time.

A question that hangs over the entire archive is one that we will never really be able to answer: why did this amazing collection of men and women, who were at the forefront of a social revolution with tremendous demands on their time, agree to sit down and talk with this white English professor from Yale about the Civil Rights Movement?

NHD: Since this is an audio archive, what is the most important aspect when it comes to listening and hearing Robert Penn Warren and his interviewees? There is something profound about this collection of voices and accents that has to do with what the Civil Rights movement looked and sounded like, right?

MF: I think that the archive is just so very human. Listening to these voices speak to us from 1964 about a massive social movement that was underway feels extraordinary. The first time I heard Warren’s interview with Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., I heard the phone ring on the tape. King says “I will need to get that.” Warren answers “Fine, I’ll hit the pause button.” I got goosebumps: it was like I was in the room with them.

Francis Coughlin reviewed the book in the Chicago Tribune in 1965. He wrote: “This is superb documentation, possibly unique in historiography. It is as if the leaders of the French, or the American, or the Russian revolutions had undergone close questioning during the stress of events and their responses embalmed in formal studies before the outcomes were decided. It is true that history may restate or revise the significance of concepts advanced and measures advocated. Yet tapes and transcripts reflect the heat of the confrontation. The actors in the current drama voice their own lines.” Coughlin’s words hold even truer for the audio archive.

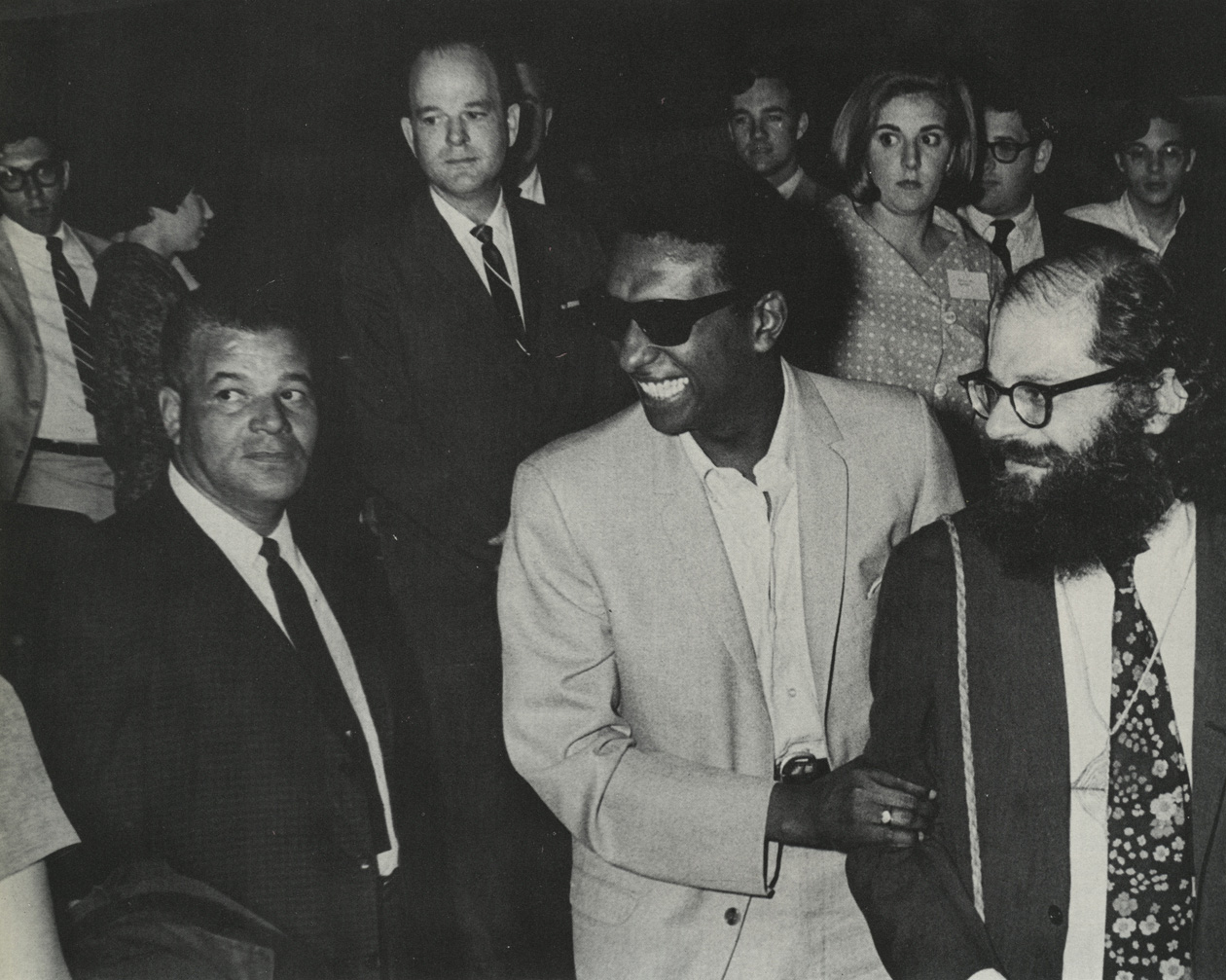

Stokely Carmichael and Allen Ginsberg at Vanderbilt University, IMPACT Symposium, April 1967. (Photo courtesy of Vanderbilt University Library Special Collections.)

NHD: What has been the impact of the Who Speaks archive and what do you hope that its legacy will be? Is the project complete or are there any plans for future development?

MF: One of the greatest impacts to date of the “Who Speaks for the Negro Digital Archive” is the fact that the book has been reissued. Though extremely well-received by critics when the book came out in 1965, it had a fairly short run with Random House. Warren was disappointed in the sales numbers for the book. In 2013, I submitted a book proposal to Yale University Press recommending that their press reissue the book. I was able to make a strong argument based in large measure on the incredible traffic that the digital archive receives. Yale accepted the proposal and the book was reissued in 2014 with an introduction by David Blight, Class of 1954 Professor of American History at Yale University and director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale. I think this is a wonderful example of a digital project bringing a book back to life.

The legacy of the site is, to my mind, the voices and the spirits of the people Warren interviewed. His project is an incredible gift to generations of scholars, teachers, students, and life-long learners who want to learn more about the men and women who were participants in this significant moment in U.S. history. In the preface to his book, Warren wrote “….I want to make my reader see, hear, and feel as immediately as possible what I saw, heard and felt.” The “Who Speaks for the Negro? Digital Archive” allows users to experience even more fully these rich and varied conversations.