Genre used to be a dirty word. Tell someone you like crime fiction, or space westerns, or even worse, romance, and they used to snub their nose at your uncultured reading preferences. That’s changed quite a bit in recent decades, and the study of genre is no longer regarded as silly or a waste of time (mostly, anyway). The question, however, of what exactly genre is is another matter entirely. Ask someone, for example, to name their favorite genre of film or literature, and they usually have one at the ready. Horror, detective, rom-com, alternate history, magical realism, Southern gothic, Midwestern spaghetti…Ahh, sorry, I made one of those up, but you get the picture.

But ask them to name the qualities which define that genre, and things sometimes get a bit wonky. Take crime fiction, for example: did you know, there are actually two uses of the phrase crime fiction? One is the general umbrella term for novels involving all manner of criminal activity, while the other is actually a sub-genre of crime fiction in which the novel centers around the criminal rather than the detective trying to solve the crime. And not all crime fiction needs a dead body: there’s white-collar crime fiction, political crime, even some Westerns could arguably be considered crime novels. So genre as a concept is a bit messy and often gets tangled up in itself, and titles which may seem to have nothing in common with each other will often be found under the same genre heading. The Conjuring, for example, is a period-piece paranormal tale about a witch’s ghost that has little in common with The Purge, a dystopian narrative about a future in which all manner of crime, including and especially murder, is legal one day a year. Yet they’re both members of the horror genre because dissimilar though they may seem, they share a few key qualities, namely ones that make my heart race and afraid of bumps in the night.

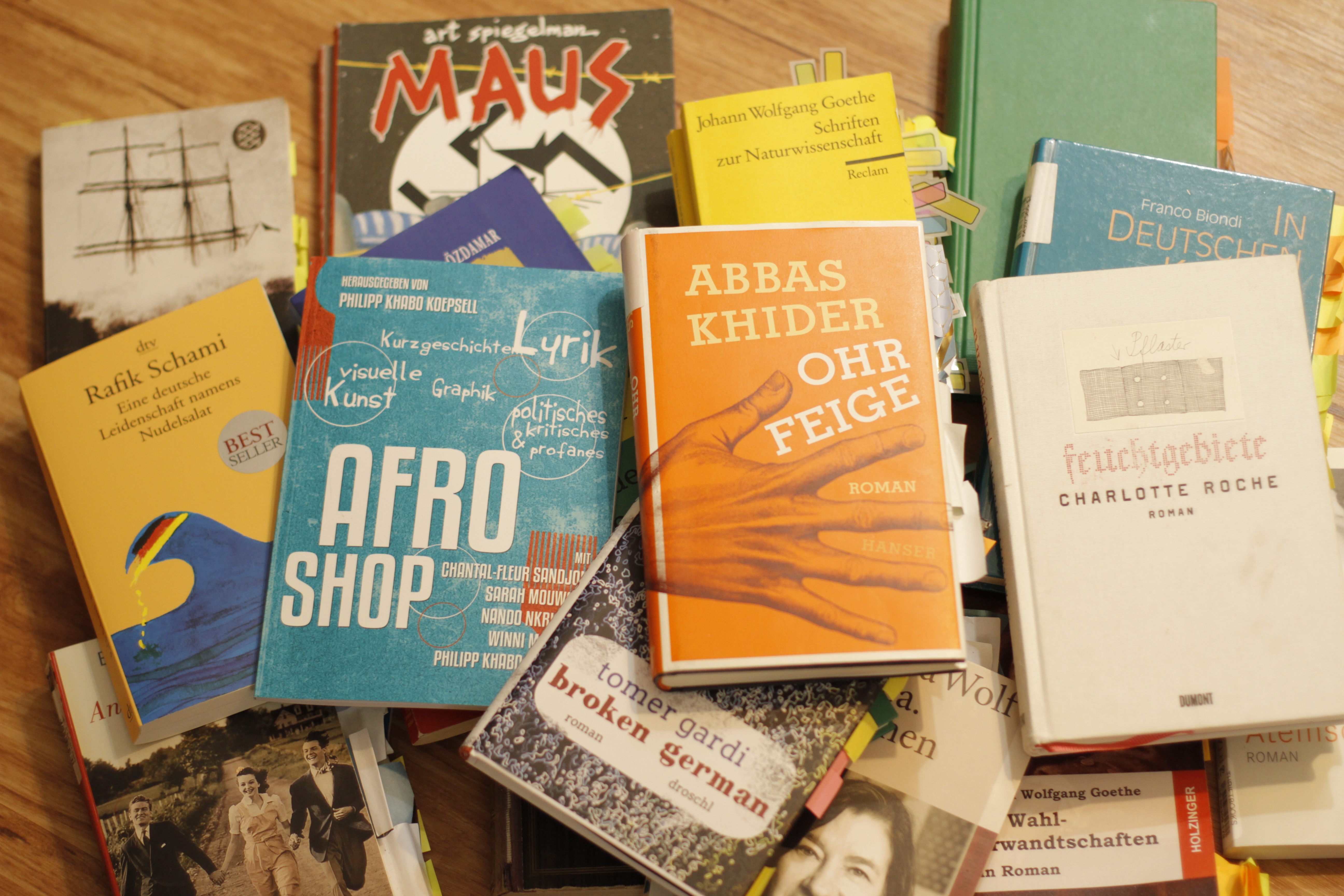

As long as works can be joined together in style, content, or form, they can at the most basic level be considered a genre. So what is it, then, that joins together a novel like Ankunft im Alltag, by Brigitte Reimann from 1961, an omniscient third-person narrative about three young adults in the DDR who work together in a factory in Hoyerswerde fresh out of school, with Feuchtgebiete by Charlotte Roche, the first-person bestselling novel from 2008 about an extremely unhygienic, hypersexual 18 year old girl as she comes to terms with her toxic relationship to her mother while in the hospital recovering from a hemorrhoid gone wrong. And what do they both have in common with Afroshop, an anthology of Afro-German poetry, art, and short fiction edited by Philipp Koepsell and published in 2014?

Arguably, nothing. But that brings us nowhere. Stylistically and formally they all differ, but content wise, they each give voice to a marginalized German experience: though DDR literature is often considered a genre of its own, and is still studied today, the mundane experiences of those who came of age after WWII are often forgotten or ignored in favor of more riveting tales of communist oppression or consumed in conversations of Ostalgie, and the day to day lives of those who grew up as the DDR did are marginalized as a result. As for Helen, the intrepid young heroine of Feuchtgebiete, she brashly and unashamedly gives voice to the type of blithe sexuality that is purposefully marginalized in favor of more ‘appropriate’ feminities that don’t so boldly disrupt notions of heteronormativity. The stories in Afro-Shop are more conventionally marginalized, but in so much as they, like Ankunft im Alltag, portray daily realities which are often ignored, and critique among other things the sort of coded language surrounding disempowered bodies like in Feuchtgebiete, they can all be considered part of a broad genre of marginalized voices within German literature.

And while their connection through content alone is alone to place these novels together, many of them are in fact stylistically related through their decisive use of language: May Ayim’s poetry plays eloquently with language in both English and German, and her mastery of the rhythms and intricacies of the German language comes through especially in her spoken word poetry. Authors like Abbas Khider, Emine Sevgi Özdamer, and Yoko Tawada all disavow notions of monolingualism by writing novels in German, a language none of them learned as children, but through which they’ve all extended meaningful representation to various marginalized groups. And new authors like Isreali-born Tomer Gardi, who is in fact still learning German, but wrote and published the book Broken German in 2016, which does not always follow the traditional rules of German grammar and follows instead the lyrical rhythms of the language and its sounds.

Be they stylistically, formally, or otherwise related, the works in this project can thus be understood as a genre of marginalized voices which has changed and evolved over time. In joining these sometimes dissimilar works together, my aim was to listen to Monika Albrecht, who in 2016 published an article which challenged essentialist views of German culture which discount the changing, heterogenous nature of German society in favor of an assumed monolithic understanding of culture. As such, my goal was not to find works which present a basic ‘us vs them’ view of German culture, but to, as Albrecht writes, show “to what extent the parameters of perception and representation of minorities are actually subject to historical transformation”(407). German culture has in fact always been varied and heterogeneous, evidence of which can be found in the works in this list. After all, to be marginalized does not mean to be nonexistent. To be marginal, something or someone must first exist and be a part of something larger, and all of these works are indeed a part of a larger tradition of German literature. They’re just not always the first names that come to mind, and that’s okay.

Sources:

Albrecht, Monika. “On the Invention of an “Essentialist View of Culture”: Thinking Outside the Prevalent Cultural Studies Discourse on Culturally and Ethnically Heterogeneous Germany.” German Quarterly, vol. 89, no. 4, 2016, pp. 395–410.