Well before the first day of class, feminist pedagogy informs course development. Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe’s theory of backward design guides instructors through the process of aligning the particularities of a course with its goals, beginning with the desired “enduring understandings” and then working backward to identify authentic evidence of learning, and finally activities that facilitate students’ production of such evidence (Wiggins and McTighe 17). In addition to the calibration of intentions, values, and beliefs with course design, this learning-centered approach tailors courses to the specific contexts created by content, students’ needs, and outside forces such as institutional requirements. The goals of backward design resonate with feminism’s attention to differences between and among people, specific contexts, and long-term goals.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty demonstrates how courses communicates issues of power, outlined in three models of syllabus design. While she focuses on women’s studies courses, her resulting categories are useful across the curriculum.

- Tourist Model: A course designed according to this approach uses the experiences of an exotic Other as “spice” to diversify a traditional curriculum. No matter how positive the intent, this strategy tends to reproduce normative assumptions about the dominance of some groups over others. Students see themselves as fundamentally separate from their objects of study, thus reiterating existing hierarchies. In others words, students “visit” content matter without having to engage with it on its own terms. In this way, “power relations and hierarchies” remain intact, while “ideas about center and margin are reproduced” (546).

- Explorer Model: A course with this design foregrounds the exotic Other, often recognizable by its very title. (Think “Women in Asia” or “Literature of the Third World.”) In this type of course, the experiences of an Other are always already established in contrast with the normative experience. That is to say words, students understand what they do as normal and what others do as exotic or strange. While these courses have a positive intent—to dedicate time and space to understudied content—they end up positioning students as an “us” and other groups as a “them.”

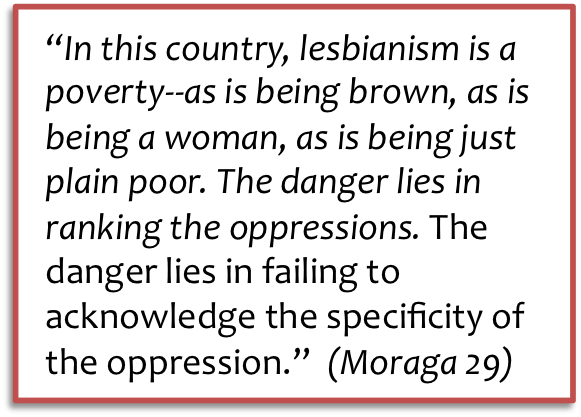

- Solidarity Model: A course designed with this model focuses in on the links and intersections between different groups, topics, histories, et al. It stays true to the complexity of knowing and being, and emphasizes “relations of mutuality, co-responsibility, and common interests, anchoring the idea of feminist solidarity” (548). This last approach ultimately helps students see the connections between the classroom and real-world struggles. By focusing on solidarity across traditional divisions of class, nation, and race, for example, it helps students grasp the interconnectedness of the human experience.

While Mohanty’s models help instructors plan relevant content most effectively, the precepts and values of feminist pedagogy can inform course design, regardless of content or discipline. For more information on how different disciplines construct knowledge and how to teach accordingly, see Chick, Haynie, and Gurung’s “From Generic to Signature Pedagogies: Teaching Disciplinary Understandings” (2009).

Next →