Home » Discovery Grants » X-Ray Diffractometer and Enchiladas

X-Ray Diffractometer and Enchiladas

Posted by anderc8 on Tuesday, April 18, 2017 in Discovery Grants, News.

Janet Macdonald is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry. Her research group studies the synthesis and surface chemistry of nanocrystals, with the aim of applying this knowledge to new solar energy capture technologies.

Janet Macdonald is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry. Her research group studies the synthesis and surface chemistry of nanocrystals, with the aim of applying this knowledge to new solar energy capture technologies.

After 21 years of experiments, on Friday, April 15, 2017, the Scintag X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) in the chemistry department was shut down for the final time. Surrounded by chemistry graduate students, faculty and staff there was a moment of genuine silence as the whirring fans slowed, the water chiller stopped gurgling and the high voltage cable was disconnected and ceased humming.

It was a sad moment. The old beast solved many chemical mysteries over the years and facilitated countless theses and publications in Nature Communications, The Journal of the American Chemical Society, ACS Nano, Polymer Chemistry, Journal of Materials Chemistry, RSC Advances and others. It is one thing for us synthetic chemists to mix chemicals in a bubbling witches’ brew in our laboratories, but it is another thing all together to figure out what we actually made. The X-ray diffractometer did just that.

An X-ray diffractometer works on a similar principle to the crystals that you hang in windows. Sunny days send rainbows scattering about the room. The XRD instrument shines X-rays at little piles of crystalline powder, and the X-rays are scattered in very specific directions, depending on the material in the powder. The detector scans through an arc measuring where those X-ray “rainbows” are, and the pattern that results can tell us exactly what material we made.

Our samples have gotten more challenging to analyze over the last 20 years. My research in chemistry is, in part, on preparing itty-bitty, nano-sized crystals, and we often needed all night on the old XRD to run a single sample. The slow instrument was consequently getting over-booked and desperate students ran samples on Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve last year. Equally frustrated were the engineers, physicists and environmental scientists who use the instrument too, and wanted to be able to do more, and faster. Peer reviewers of our papers and grants were demanding and expecting more than the old beast could readily provide.

With my voice and the support of 19 of my like-minded colleagues, I convinced the Discovery Grant program and chairs of six different departments and institutes to buy a new instrument for all of us to use. Shout out to Provost Wente, Chemistry, Vanderbilt Institute of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Earth and Environmental Sciences and The Laboratory for Systems Integrity and Reliability!

When I went to test drive the new instrument at the Rigaku headquarters in Houston, I consulted the broad user group and went armed with examples of our toughest, meanest samples. The new instrument, aptly named “Smart Lab,” got better results in 10 minutes than what took us 12 hours on the old one. I was able to measure mind-boggling, ultra-thin samples that were only 10s of atoms thick. The computer interface and instrument design were user-friendly, so our students will be able to perform high-end experiments with autonomy and minimal training.

To say the least, I geeked out. It was difficult to contain myself.

But there is something you should know about me. I lived in Jerusalem for two years doing a postdoctoral fellowship at The Hebrew University. I learned how to haggle like a local. Despite my geeky excitement, I put on my stoic face, went into full Israeli mode, and visited other vendors over the next few months to negotiate some fantastic bells and whistles.

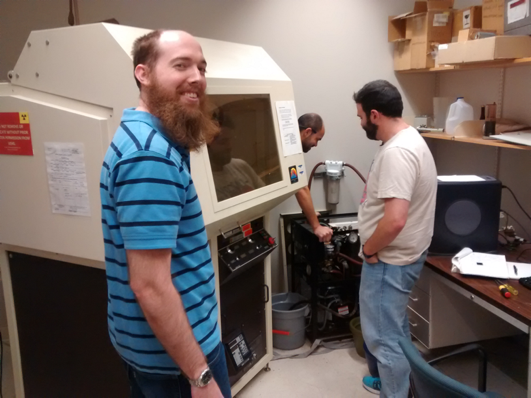

Graduate Student Evan Robinson looks on as the old X-Ray Diffractometer is decommissioned by Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Emil Hernandez and Graduate Student Andrew La Croix. Evan isn’t too sad to see the old beast go, and is pretty excited about the new XRD and how much faster his experiments will be.

I am happy to report that involved and complicated measurements will be easy, quick and standard. We will have new experimental tricks up our sleeves that will leave others green with envy. I’ve been dreaming up experiments and projects I wouldn’t have previously contemplated, and I know others are, too. The Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering just recruited a new faculty member whom was practically drooling in my office last month when I told him about the new instrument.

When the old instrument was finally shut down for the last time, and that hush fell across the room, the first words to break the silence were “When does the new one get here?”

The answer is May 1, my friends. Then the fun begins. I’ll let you know when we start doing some mind-blowing science.

Mourning is often accompanied by food. While cleaning out the instrument room we unexpectedly came across a recipe for enchiladas tucked between the hoard of ancient technical manuals and floppy disks. I made some of the enchiladas for the Scintag XRD “wake,” as it were. They disappeared before I got a chance to take a picture as graduate students are always hungry for free food.

I am looking forward to hearing memories of XRDs, and recipe reviews below!

XRD Enchiladas

2 cups of cooked chopped chicken

½ cup sliced roasted red bell peppers (7.25 oz jar)

1 cup of sour cream

8 (8 inch) flour tortillas

6 oz (1/2 cup) shredded Monterey Jack cheese

1 (4.5 oz) can chopped green chillies

1 (10oz) can enchilada sauce

6 oz (1/2 cup) shredded cheddar cheese

- Heat oven to 350 degrees. Spray 13×9 baking dish with non-stick cooking spray. In a medium bowl, combine chicken, Monterey Jack cheese, roasted peppers, chillies and sour cream. Mix well.

- Spread about 2 tablespoons of enchilada sauce on each tortilla. Top each with ½ cup chicken mixture. Roll up tortilla arrange seam side down in sprayed baking dish. Top enchiladas with any remaining enchilada sauce. Sprinkle with cheddar cheese. Spray sheet of foil with cooking spray; cover baking dish with foil, spayed side down.

- Bake at 350 degrees for 45 to 60 minutes or until thoroughly heated. If desired, serve topped with lettuce, tomato, avocado and additional sour cream.