Home » News » Did they practice what they preached? The “father of bioethics” tells all

Did they practice what they preached? The “father of bioethics” tells all

Posted by anderc8 on Monday, August 21, 2017 in News, Research Scholar Grants.

Written by Laura Stark, Associate Professor at the Center for Medicine, Health and Society

Written by Laura Stark, Associate Professor at the Center for Medicine, Health and Society

Dr. Henry K. Beecher was a powerbroker of the American medical establishment in the decades after World War II. He was the head of anesthesiology at Harvard and well-connected at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), but Beecher is perhaps best remembered as the father of modern bioethics. In 1966, he published an article that exposed research he deemed unethical being performed by his medical colleagues across the country. What is surprising in retrospect, in addition to the studies themselves, is that a fixture of the scientific establishment could think beyond the ethical orthodoxies he had learned in school. How did he shuffle out of lockstep with his postwar colleagues and mentors? And why would he jeopardize his own secure position, not to mention his friendships, by challenging postwar paternalism—in ways that reshaped how medicine is practiced in the present day?

Dr. Henry Knowles Beecher, circa 1962. (Photo credit: Countway Library Special Collections, Harvard.)

With the support of a summer stipend from the Research Scholars Grants program, I dug up answers to these and other questions in Beecher’s personal papers in Boston, Mass. There, I unearthed the backstory of Beecher’s ethics using on his own private letters, and finished research on other projects—all of which explore the history of ethics as it is practiced in contrast to ethics as it is preached. The story I found buried in Beecher’s private papers was quite a surprise, and my findings were published in The Lancet at the end of June 2016.

My time in Boston was important for a second reason. Beecher’s personal papers are housed at Harvard’s Countway Library Center for the History of Medicine, which, with the help of the Vanderbilt Library System, is archiving a unique collection of historical resources that I created over the past six years. My original historical collection includes old letters, pictures, diaries and other materials with people who served as “human subjects” of government medical experiments at NIH during Beecher’s time. The collection also includes an oral history of interviews with those former research participants, as well as the scientists and administrators who knew them, including interviews I completed for the collection while in Boston. During the summer, I was able to work with the team of archivists at Harvard building the digital repository. At Vanderbilt, the archive team continued to prepare my materials for the collection and to build a showcase of the collection now on view at Heard Library. In addition to the RSG program funding, Vanderbilt’s Library Dean’s Fellows Program gave generous support—of funding, time, expertise and good humor! I extend special thanks to Dr. Jenifer Dodd, the project’s Dean’s Fellow in 2015-16 and recent graduate of the History Department’s PhD program, who has returned to Vanderbilt as a Mellon postdoctoral fellow in Vanderbilt’s new Center for Digital Humanities.

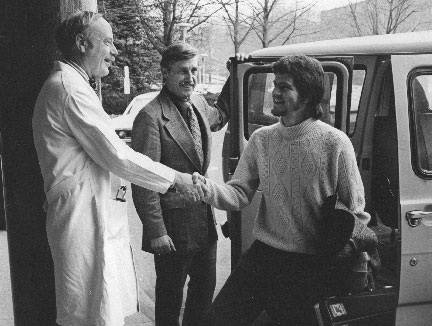

Thomas Chalmers (who was a rival of Beecher and clinical director at the NIH Clinical Center), Frank James (who was a “normal control” subject) and Delbert Nye (NIH’s supervisor of the Normal Volunteer Patient Program). (Photo credit: US National Institutes of Health)

My research on Beecher and on the people who stories are seldom told—those who served in medical experiments—illustrates how perspectives from the past can serve as a resource in the present as we think beyond our own current ethical orthodoxies. Since 2011, the federal government has been updating the 1974 National Research Act, which was the first U.S. law for the treatment of human-subjects and–over the past 40 years–has seen no substantial revisions. This past fall (2016), I accepted an invitation to speak about my research at a national Town Hall meeting, sponsored by NIH, designed to receive public input on how to revise regulations.

Vanderbilt’s support of research into the past can affect current public policy, as well as the moral life of our campus community, showing how history lives with us in the present and can help shape a better future.

I encourage readers to join the conversation by asking a question or leaving a comment in the space provided below.