Home » News » A Culture of Litigation: Arguing Daily Life

A Culture of Litigation: Arguing Daily Life

Posted by anderc8 on Wednesday, April 18, 2018 in News, Research Scholar Grants.

Mark Schoenfeld

Written by Mark Schoenfield, Professor of English

In Samuel Foote’s 1770 The Lame Lover, a neophyte attorney explains that “a great lawyer’s business is always to make the choice of the wrong,” since “a good cause can speak for itself, whilst a bad one demands an able counsellor to give it a colour.” Aided by a Vanderbilt University Research Scholars Grant, I explored various archives concerning British culture, 1770-1835, for my project, A Culture of Litigation.

During visits to the Huntington Library in Pasadena, Calif., and the National Library of Scotland, in Edinburgh, I read accounts, both real and fictional, demonizing and glorifying that “palladium of justice,” the trial by jury. I found significant legal cases that reshaped public understandings of property, scandalized the British public about aristocratic ethics, and made lawyers famous and rich and lionized. In this blog, however, I will share two cases that illustrate the extent to which jury trials had become a part of daily life and its arbitrations.

On July 30, 1819, a shoemaker brought an action against a “reverend intruder” for burning two of his books. It seems a clergyman, Mr. Venables, called upon the Drake residence while the shoemaker was away, and looking around, asked his wife for permission to burn two “bad” books (alas, unidentified in the trial, according to newspaper accounts). When she demurred, he assured her that he would replace them with two good books. According to the only witness called, “Mrs. Drake said it was a matter of indifference, she had rather have a good book.” Mr. Venables burned the books and left before the shoemaker returned. In his opening address, Mr. Drake’s lawyer declared the case was brought “not to recover damages, but to teach officious and overzealous men that their enthusiasm furnished them with no excuse for intruding with presumption and arrogance into the houses of their neighbors.” What else, the lawyer queried, “should induce him to be guilty of so gross a breach of good manners?” Declaring that he “respected religion as [much] as any man,” he opined he did not like to see her “tight laced and choked with starch.” Summing up, he assured the jury that the defendant “had infringed upon the rights of an Englishman and must now take the consequences.”

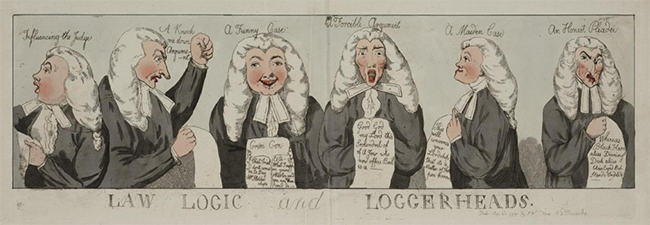

“Law, Logic and Loggerheads” (1791), The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

The attorney for the defense, after deriding his opposition’s hyperbole, assured the jury that “the duty of every clergyman” required “ascertaining” his flock’s moral instruction. He also declared seeking legal remedy was not asserting English rights, but on the contrary, simply bad—and “unmanly”—manners. He concluded that he, the defense counsel, would “have been the first” to burn an “amorous poem or an invidious novel.” The judge declared “No Englishman need tamely suffer his house to be ransacked by a clergyman, nor (if he could help it) by his wife,” and recommended the smallest possible damages; the jury returned for one farthing—plus costs—for the cobbler. In part because of its comical staging, this trial presents many key issues of English litigation: the indeterminate line between breaches of manners and legal crimes; the significance of intent; the tension of church and state as moral litigators; and the value of reputation. Its rhetorical gestures reflect those of the most serious cases of sedition (which is tangentially mentioned in the case) and of bodily assault and libel (both of which are also alluded to). It reiterates the question of reading as socially dangerous, and the dynamic of gender in the household as a miniature of the body politic. (Stamford Mercury, August 6,1819; Examiner, August 8,1819).

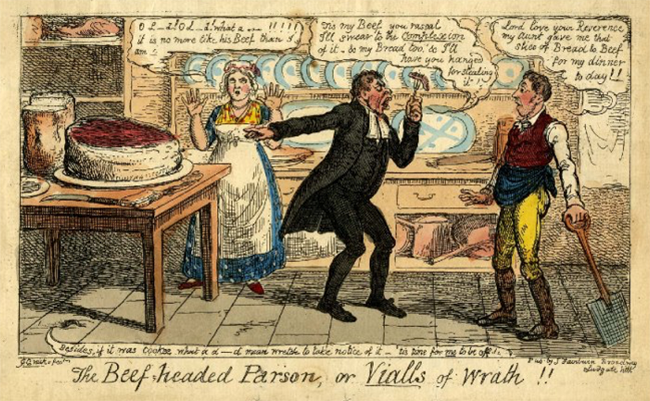

A second example: The Reverend Thomas Vialls was a suspicious parson. Finding his gardener’s lunch was a slice of corned beef on bread, he immediately confiscated it to compare it with his own round of beef and loaf of bread. The similarity was, at least to him, striking and improbable enough to bring an action for theft. At trial, he declared, “I know the beef to be mine from its complexion!” After the gardener, James Sharpe, was acquitted, he brought a suit against Vialls for malicious prosecution. Charles Phillips, speaking for the plaintiff, began by noting his own delicate position of “advocating the cause of humble poverty against pampered oppression.” His solution was to render the tale comic. Turning to Viall’s testimony of his beef’s complexion, he conceded “the merit of originality”:

Gentlemen, in poetry, I have read of the tints of the morning, the verdure of the fields, the blush of the rose and the emerald of the sea, but never until now did I hear of the complexion of a cold corned round of beef. I dare say there was a lily whiteness about the fat, and a modest, saltpetre, Aurora-like redness about the lean. (Fairburn’s Edition of [Sharpe v Vialls]).

The Beef-Headed Parson, George Cruikshank. British Museum

Phillips calculated his ridicule to exploit assumptions about charity, and about the jury as a guarantor not only of justice, but of the social order. The verdict of this second trial was not trivial; the jury found, “almost instantly” in favor of the gardener for £50, probably more than two years of his salary, although only a nuisance for Vialls, except for bearing costs and the public humiliation. Afterwards, John Fairburn, famous for elaborate and wildly popular editions of scurrilous Crim Con trials, published the case. Underscoring its social significance, a poem was appended to the trial, “The Twickenham Parson; or Beef! Beef! Beef!” It reiterated the issue of charity as a social value, and highlighted Viall’s corruption by a conclusion in which the two trials are conflated and crime and punishment are cleverly inverted:

The worthy PARSON curs’d such times in grief,

And curs’d the jury too, when he must pay

Full fifty pounds for one thin slice of beef,

Which from a servant he had filch’d away.

Republished elsewhere, including the widely-circulating Spirit of the Public Journals, the poem, by making the parson a domestic tyrant and the jury the silent hero, extends the case’s reach as an exemplar of social dynamics.