Home » News » A Musical Awakening

A Musical Awakening

Posted by anderc8 on Wednesday, May 24, 2017 in News, TIPs 2015.

Written by Alexander Chern, M.D. candidate at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Written by Alexander Chern, M.D. candidate at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

About a year ago, in a crosswalk at the corner of Natchez and Blakemore, I was hit by a car. I was hospitalized for a month after sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and other serious injuries. When I woke from my coma, the first thing I remember was asking my mother for my computer. I went on YouTube and listened to Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, the Pastoral Symphony.

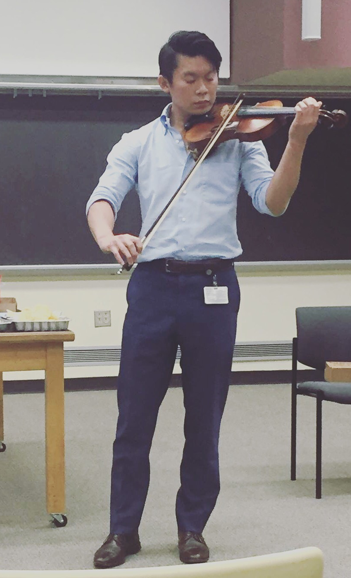

I listened to more music over the next three months than I had the previous three years, rediscovering my love for music. I played the violin growing up. I took lessons, participated in orchestra, played chamber music and attended music camps. In college, I played in the Yale Symphony Orchestra, taught lessons to underserved children and studied with Kyung Yu, a faculty member of the Yale School of Music. Unfortunately, during the first three years of medical school, I barely touched my violin. I was so busy that I lost my identity as a musician.

Upon returning home after the accident, I picked up my violin and started playing again. At first, my fingers felt like Jell-o, and I feared my TBI impacted my ability to play. I later realized this was due to lack of practice, not the accident.

Two months before the accident, I applied for funding from the Medical Scholars Program to conduct research in the Music Cognition Lab under the guidance of Dr. Reyna Gordon, Ph.D. in the Department of Otolaryngology. I first read about the lab in a Vanderbilt Reporter article about Program for Music, Mind & Society (MMS), an initiative led by Dr. Gordon and Dr. Ron Eavey, M.D. This multi-disciplinary team, composed of researchers across many fields at Vanderbilt, has an important mission – to study how music impacts our brains, minds, health and behavior.

With Dr. Gordon and Dr. Robert Labadie, M.D., Ph.D. as mentors, I am examining the influence of rhythm on grammar in typically developing children and children with cochlear implants (CI), surgically implanted devices that provide a sense of sound to those with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss. Our collaborators in France, Dr. Barbara Tillmann, Ph.D., and her research group, found that children with dyslexia, specific language impairment and typical development perform better on grammaticality judgment after first listening to rhythmically regular musical stimuli compared to rhythmically irregular musical stimuli, as if they were primed by the regular stimuli. Grammaticality judgment tests consist of grammatical and ungrammatical sentences. Children are asked to indicate which are correct and which are incorrect. My project aims to determine if this Rhythmic Facilitation Paradigm extends to English-speaking children and children with CI. Though a vast range of language ability is observed, many kids with CI have language development difficulties compared to their normal-hearing peers. We have promising results in typically developing participants; testing is underway in children with CI. Understanding such mechanisms for auditory processing is paramount for facilitating communication in patients with CI and developmental language disorders.

Over the past year, I have also worked with Dr. Joseph Schlesinger, M.D., another researcher in MMS. A jazz pianist, VUMC anesthesiologist and critical care physician, Dr. Schlesinger is working on improving patient safety by using music perception and cognition to improve alarm design. Our work examines how clinicians perceive urgency in the clinical space.

Over the past year, I have also worked with Dr. Joseph Schlesinger, M.D., another researcher in MMS. A jazz pianist, VUMC anesthesiologist and critical care physician, Dr. Schlesinger is working on improving patient safety by using music perception and cognition to improve alarm design. Our work examines how clinicians perceive urgency in the clinical space.

My time working with researchers in MMS has shown that I can consolidate my passions for music and medicine in my future career as an academic physician. For the first time in my life, music has become something much more than a chore or something I did for fun; it is now something I think critically about and incorporate into the realm of medicine. I not only rediscovered music, but I also began looking at music through different lenses – both humanistic and scientific.

I often wondered why I took comfort in Beethoven’s Pastoral, as opposed to another piece of music, while hospitalized. While I may never know the extent of the mechanisms at work in my musical brain, I have a hypothesis. Upon waking, my memory was fuzzy and I was confused about why I was in a hospital bed with various injuries. Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony was written simultaneously with and in stark contrast to his Fifth Symphony, well known for its alleged “fate knocking at the door” motif. The Pastoral Symphony was soothing and took my mind off trying to piece together my thoughts on the accident. I found comfort in the simplistic sounds that were evocative of a rustic world of cheerful feelings, gentle streams, dancing shepherds and frightening thunderstorms. When I was younger, I played Beethoven’s Spring Sonata and Romance No. 2 – pieces also composed in F major. The key of F major has long held associations with nature –the third movement of Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, Scene in the Country and J.S. Bach’s Pastorale are in this key. Beethoven famously noted that the Pastoral had “more an expression of feeling than painting.” Perhaps this honest and simple expression of the countryside put me at ease.

Whatever the reason, my experience following the accident and research in the Music Cognition Lab has cemented my belief in the necessity of studying how music impacts behavior and its implications on health. I feel lucky and excited to embark on the next part of my journey with music and medicine.