Mystery Ticket Shortage

Posted by John Vrooman on Wednesday, April 11, 2018 in National Hockey League.

Interview with Toronto Star.

We’re revealing that MLSE has designated an unknown number of season ticket holders “commercial resellers” and marked up their tickets 30% for next season. They also offer to cancel the markup if the ticket holder joins a “preferred reseller program” which hasn’t been well defined yet, but many suspect will involve TickerMaster’s reseller platform, which would give a cut of the resale profits back to the Leafs.

I’d be very interested in hearing your thoughts on this carrot and stick approach to brokers, who say they’ve stuck with the team through the lean years, when their reselling was tolerated and even encouraged, and now that the team is good, they’re being penalized.

The mystery ticket shortage is probably the combination of two effects.

First, the option to buy post-season playoff ducats is an important part of the Leafs’ season ticket package and already reflected in the season ticket price set in the primary (box office) market by the Leafs. Season ticket holders retain the valuable option to use the tickets or sell them in the secondary market depending on the quality of the game. There are probably plenty of playoff tickets available for the Bruins series (and possibly beyond) in the secondary reseller’s market at a higher (lower) price and potential gains (or losses) for the season-ticket holders.

The season-ticket is an implicit contract for the fans to enjoy the discounted post season perks in good seasons in exchange for overpaying for worthless options in bad seasons. All Leafs’ season-ticket holders have access to playoff tickets usually at a primary market discount reflecting the length of the season-ticket commitment. The Leafs have already taken their cut in the primary market (box office) price for the relative certainty of the season ticket. The Leafs are effectively shifting the Stanley Cup playoff risk to the regular season-ticket holders in exchange for a discounted post season option price.

The second effect comes from the distribution of primary playoff tickets to the Leafs’ sponsors, friends and families. Many clubs treat the post season as a celebration that rewards regular season sponsors. In many cases those complimentary tickets will also find their way into the post-season secondary market where the prices fluctuate to reflect the quality of the series and the game.

V

Followup.

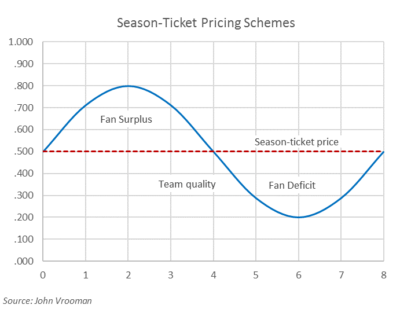

The season-ticket is an implicit contract between the Leafs (MLSE) and their fans to enjoy the discounted post season perks in good seasons in exchange for overpaying for worthless options in bad seasons. In theory, the most efficient profit max price for the Leafs is set where fans enjoy a fan surplus (quality > price) that is exactly equal to a fan deficit (quality < price) in the graph where the area under red line is equal to area under blue line.

In the risky business of primary market ticket pricing, MLSE will shift Lord Stanley’s playoff risk (the variance in blue-line team quality in the graph) to regular season-ticket holders in exchange for a discounted post-season option price. Professional clubs are usually willing to trade greater sums of risky money (variable area below blue line) for smaller amounts of certain cash money (risk-free area below red line). If the primary ticket price is set properly there is no risk-adjusted cash flow left on the table (surplus = deficit) and there is no financial room for commercial resellers in a formal secondary market.

The existence of a secondary market for resellers is prima facie evidence of the inefficiency of the primary market price because MLSE is leaving relatively certain money on the table (surplus > deficit). The existence of a secondary market for season-ticket holders also allows primary season-ticket buyers the option to sell their tickets. MLSE has already taken their cut in the primary market (box office) price in exchange for the relative certainty of the season ticket (constant area below the flat red line is slightly smaller than variable area under blue line).

More recently (MLSE began dynamic pricing in 2013) clubs in leagues with longer seasons have sought to recover all of the money left on (or under) the table by using variable or dynamic pricing schemes. In effect, the primary market sellers are virtually replicating the secondary market pricing by charging higher prices for good games/seasons and discounts for the games/seasons that don’t matter (variable area under blue line).

In theory this dynamic approach is mathematically equivalent to the efficient season-ticket price. Efficient primary sellers will charge a variable primary price along the blue line that yields the same cash flow under the constant red line. Dynamic pricing is used in MLB (Blue jays), NBA (Raptors), NHL (Leafs) and not in the NFL, where PSLs serve as a down payment for discounted season tickets. The goal of dynamic pricing is to use primary market pricing schemes to recapture the potential gains the left on or under the table in the demand driven secondary market.

Season-ticket pricing and variable/dynamic ticket pricing are equivalent price discrimination alternatives but they rarely are used together because the variable/dynamic pricing scheme violates the implicit contract of the season ticket. If MLSE captures the fan surplus by increasing the season ticket price during good games/seasons and leaves the fan deficit by not offering lower prices during bad games/seasons, then the implicit season ticket contract is bogus and post-season options are relatively worthless.

This is why MLSE is trying to separate the secondary market commercial resellers from the season-ticket resellers by charging the commercial sellers a premium of up to 30 percent. The Leafs are offering to rescind the surtax if the commercial resellers use a secondary market platform controlled by MLSE. This stick-carrot pricing whiplash is a not-so-subtle attempt by MLSE to use a hybrid variable/dynamic pricing scheme to internalize (recapture) the potential secondary market gains left on the table by an inefficient primary pricing scheme, without damaging the implicit contract of the Leafs’ traditional season-ticket base.

V

©2025 Vanderbilt University · John Vrooman

Site Development: University Web Communications