High-Leverage Practices in Special Education

What are high-leverage practices (HLP)? The Council for Exceptional Children and the CEEDAR Center published a book in 2017 that is all about high-leverage practices. They describe HLP as ““a set of practices that are fundamental to support K–12 student learning, and that can be taught, learned, and implemented by those entering the profession” (Windschitl, Thompson, Braaten, & Stroupe, 2012).

HLPs focus in the aspects of special education such as collaboration, assessment, social-emotional behavior supports and instruction. In order for a practice to be considered “high-leverage,” they must meet the following criteria:

- Focus directly on instructional practices

- Occur with high frequency in teaching in any setting

- Be research-based and known to foster student engagement and learning

- Be broadly applicable and usable in any content area or approach to teaching

- Be fundamental to effective teaching when executed skillfully

(Source: McLesky et. al., 2017)

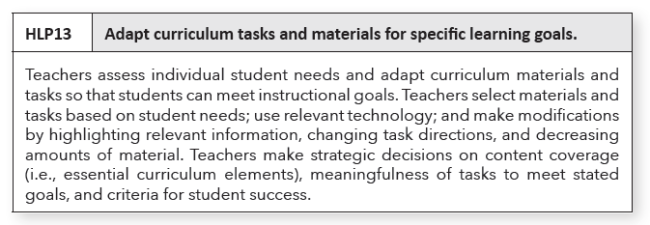

Let’s examine one of the high-leverage practices focused on adapting instruction to meet student needs. Making adjustments to students instruction is the corner stone of Data-Based Individualization. Teachers know that students need changes to curriculum and materials to make them both accessible and to impact their learning. High-Leverage Practice 13 examines this in detail. Through examination fo research and supporting literature the CEC has identified making instructional changes as one that all teachers can use in the classroom to impact student outcomes. Along with making adaptations, data should be driving the choice to adapt materials and tasks. Think about it like this. If you are teaching your child to ride their bike, you wouldn’t just have a feeling that they can ride it without training wheels. You would carefully observe, maybe even collect some data on number of falls, and use this data to drive the decision to take the training wheels off the bike. The same goes for adapting tasks and materials. Use data to drive these decisions.

(Source: McLesky et. al., 2017)

This is just one example of the 22 HLP that the CEC and the CEEDAR center have come up with. To explore in depth these high-leverage practices and how they are implemented in the classroom, the CEC and CEEDAR center have created a comprehensive website. The website includes all of the high-leverage practices, resources and additional materials to get started. They have broken each of the topics down and provided short and comprehensive information about what the practices are and their support from the research.

(Source: High-Leverage Practices in Special Education)

To access the High-Leverage Practices in Special Education website, click here.

Along with the website, the CEC and CEEDAR center have created a print and digital book called “High Leverage Practices in Special Education.” The book is available for purchase from The Council for Exceptional Children.

To access the CEC’s store to purchase High-Leverage Practices in Special Education, click here.

High-leverage practices are focus on the aspects of special education surrounding collaboration, assessment, social-emotional behavior supports and instruction. Each of these practices are backed by research. Consider using these practices in your classroom to support struggling students.

References:

McLeskey, J., Barringer, M-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017, January). High-leverage

practices in special education. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center.

Riccomini, P., Morano, S., & Hughes, C. (2017). Big ideas in special education: Specially designed instruction, high-leverage practices, explicit instruction, and intensive instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50, 20–27.

Leverage Practices in Special Education. (n.d.). Retrieved November 4, 2019, from https://highleveragepractices.org/.

Sayeski, K. L. (2018). Putting high-leverage practices into practice. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 50(4), 169–171.