What is Data-Based Individualization?

![]()

Danielson and Rosenquist (2014) define data-based individualization as “a systematic method for using assessment data to determine when and how to intensify intervention in reading, mathematics and behavior.” Data-based individualization (DBI) is just that. It’s using data from assessments and progress monitoring to make instructional adaptations for students who do not respond to instruction.

Data-based individualization is different from other interventions in that you are making instructional adaptations to an already validated academic or behavioral intervention program. You are not creating a program from scratch or using a single strategy or intervention program. This process is not static and through continuous assessment and data collection, adaptations are always being made to make sure that instruction is meeting the needs or learners. DBI is not a process for all students, this is a process that is for students with the most intensive academic and behavioral needs.

An emphasis should be placed on the word “data” in data-based individualization. The instructional adaptations that you make to an intervention are not based on assumptions or intuition about what a student needs. Decisions are based on data from consistent progress monitoring with a validated progress monitoring tool. Central to collecting and analyzing this data is using it to make decisions. If data is collected and never used but decisions are being made, the likelihood that those decisions will have a positive impact are low. Data-driven decision increases the likelihood that instructional changes will have positive impacts on student outcomes.

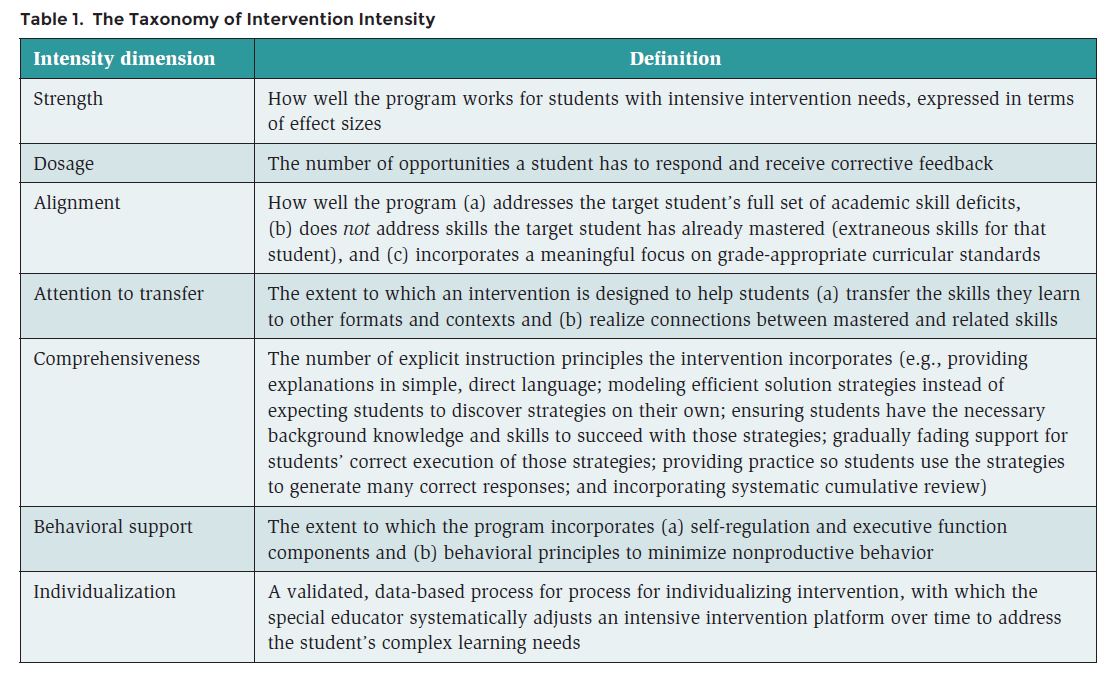

To give more context about data-based individualization let’s take a look at The Taxonomy of Intervention. Fuchs, Fuchs, and Malone (2012) identified seven principle for building and assessing intensive intervention.

(Image reproduced with the expressed written permission of the Office of Professional Publication for the Council for Exceptional Children)

These principles, also know as The Taxonomy of Intensive Intervention, are adjustments that can be made to Tier II interventions in order to meet the needs of students with significant learning problems. We are going to explore each of them in detail.

Strength refers to the strength of an intervention program and it’s known effects for learners. The strengths of intervention are reported in effect sizes in research. Intervention programs that have a strong research base and demonstrate larger effect sizes for students are more likely to be impactful for students and require less adaptations. Think about strength like this…if you were shopping for an effective product to treat wrinkles on your face you wouldn’t just pick anything off the shelf. You would consider the needs of your skin, the results you are looking for and what additional products you would need to support the products effectiveness. Strength of intervention is applying the same principle to academic programs. You wouldn’t just take anything off the shelf for students with intensive needs. You would look for effectiveness and research to back claims and see what additional adjustments you would need to make the program most effective.

This principle of intensive intervention is examine groups size, number of minutes spent on instruction, and how often intensive instruction is provided to a student. Each of these impact the amount of time the student will have to receive instruction, opportunities to practice skills and the amount of feedback they will receive on their performance. These changes to intervention programs can be the first step in intensifying an intervention. Increasing the amount of time a students receives instruction and the frequency of sessions can impact the effectiveness of the intervention.

When looking at an intervention program, careful consideration needs to be made to what skills the intervention does and does not address and if it incorporates a focus on curriculum standards. If you are looking to address a students need for fluency, you wouldn’t select a program that focuses solely on phonics with no consideration of fluency. Along with targeting the skills a student needs, a consideration needs to be made to how the skill connects with the students grade level. If you are working with a 3rd grade student who is still requiring instruction on additive schema, you might consider aligning the intervention program with content in their grade level math class. Alignment of intensive intervention to grade level content makes a stronger connection between the skills the student needs to work on with it’s connecting to their current grade level.

Attention to transfer looks at how an intervention program helps students to transfer skills to other contexts. If a program is focusing solely on segmenting and decoding but not on whole word reading, the likelihood of the student transferring their decoding skills to word or sentence reading is very low. Think about it like this…when you learn to close a door, the skills for closing a door apply to different contexts. You wouldn’t just close the door to your house and not close the door to your car. The skills for closing a door transfer to different context. Transfer is equally important in intervention programs. The skills being taught to students need to be able to transfer to other contexts.

Attention to transfer looks at how an intervention program helps students to transfer skills to other contexts. If a program is focusing solely on segmenting and decoding but not on whole word reading, the likelihood of the student transferring their decoding skills to word or sentence reading is very low. Think about it like this…when you learn to close a door, the skills for closing a door apply to different contexts. You wouldn’t just close the door to your house and not close the door to your car. The skills for closing a door transfer to different context. Transfer is equally important in intervention programs. The skills being taught to students need to be able to transfer to other contexts.

When you are teaching students, you don’t just use one or two instructional principles to teach new content. Comprehensiveness examines how many principles of explicit instruction are found within a program. Elements of explicit instruction include extensive modeling of skills, using concise language, providing student guided and independent practice of new skills and many more. To find information about explicit instruction, visit the case study and information here.

Students who are experiencing academic difficulty often times need support in behavioral context such as motivation and self-regulation. Interventions that address academic with behavioral supports increase the likelihood that the student will find success with the intervention program. If you are wanting to learn how to run and you’ve never done it before, you might have trouble getting started. However, if you use a beginning runners program with built in encouragement every 2 minutes, you are more likely to start running. The same is principle is important for struggling learners. Teaching behavioral skills that will support a learner during the learning process increase their likelihood of being successful.

The last and most recognizable feature of DBI is individualization. To implement DBI for a student, a teacher focuses on collecting data, analyzing the effectiveness of a program and making changes based on that student only. DBI is not a process that can be applied to a group. This process of DBI is continuous and always looking at what your individual learner needs. A doctor wouldn’t prescribe a group of patients the same medication to treat different problems. A doctor looks at what medication will decrease your symptoms and tailor medication to your individual needs. DBI is the same progress. You look at the data, see if additional tests are needed, implement a intervention, test its effectiveness and then repeat the process if the needed.

The last and most recognizable feature of DBI is individualization. To implement DBI for a student, a teacher focuses on collecting data, analyzing the effectiveness of a program and making changes based on that student only. DBI is not a process that can be applied to a group. This process of DBI is continuous and always looking at what your individual learner needs. A doctor wouldn’t prescribe a group of patients the same medication to treat different problems. A doctor looks at what medication will decrease your symptoms and tailor medication to your individual needs. DBI is the same progress. You look at the data, see if additional tests are needed, implement a intervention, test its effectiveness and then repeat the process if the needed.

The table below includes some articles to provide more context of data-based individualization and data-based decision making:

Click on the article title to access the publication.

|

Article Name: |

Authors: |

Article Description: |

|

|

Lemons, Kearns & Davidson (2013) |

This article examines the DBI process through a case study from a real experience in the teaching field |

|

Lemons, Sinclair & Gesel (2017) |

This document provides an overview of the Center’s accomplishments during the initial funding cycle and to highlight a set of lessons learned from the 26 schools that implemented intensive intervention |

|

|

|

Powell & Stecker (2014) |

Examines the DBI process through a case study from a real experience in the teaching field through the lens of math |

|

Intensive Interventions for Students Struggling in Reading and Mathematics – A Practice Guide

|

Vaughn, Wanzek & Murray (2012) |

This publication on intensive interventions can inform the design, delivery, and use of evidence-based interventions with students, including those with disabilities and those who struggle with mastering today’s rigorous reading, literacy, and mathematics standards. |

|

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions: Using Data to Make Instructional Decisions for Struggling Readers |

Filderman & Toste (2017) |

Applying the DBI process to struggling readers with examples through a case study |

|

What do Beginning Special Educators Need to Know About Intensive Reading Interventions?

|

Coyne & Koriakin (2017) |

Examines the complexity of reading and support skills acquisition with DBI |

|

What is Intensive Instruction and Why Is It Important?

|

Fuchs, Fuchs & Vaughn (2014) |

Examines the DBI process through MTSS (Tier System) |

References:

Coyne, M. D., & Koriakin, T. A. (2017). What Do Beginning Special Educators Need to Know About Intensive Reading Interventions? TEACHING Exceptional Children, 49(4), 239–248

Danielson, L., Wexler, L., Rosenquist, C. (2014). Introduction to the TEC special issue on data-based individualization. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 46(4), 6–12.

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Vaughn, S. (2014). What is intensive instruction and why is it important? Teaching Exceptional Children, 46(4), 13–18.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., & Malone, A. S. (2017). The taxonomy of intervention intensity. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50, 35–43.

Filderman, M. J., & Toste, J. R. (2018). Decisions, Decisions, Decisions: Using Data to Make Instructional Decisions for Struggling Readers. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 50(3), 130–140.

Lemons, C. J., Kearns, D. M., & Davidson, K. A. (2014). Data-based individualization in reading: Intensifying intervention for students with significant reading disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 46(4), 20–29.

Lemons, C., Sinclair, A., Gesel, S., Gruner Gandhi, A., & Danielson, L. (2017). Supporting implementation of data-based individualization: Lessons learned from NCIPs first five years. Retrieved from http://www.intensiveintervention.org/sites/ default/files/NCII_LessonsLearned_2.0_508.pdf on October 26, 2019.

Powell, S. R., & Stecker, P. M. (2014). Using Data-Based Individualization to Intensify Mathematics Intervention for Students With Disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 46(4), 31–37.

Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., Murray, C. S., Roberts, G. (2012). Intensive interventions for students struggling in reading and mathematics: A practice guide. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction.