Home » HART » Lillian Boyle: Reflections on the Artistic Rhythms of Southern France, Part I

Lillian Boyle: Reflections on the Artistic Rhythms of Southern France, Part I

Posted by vrcvanderbilt on Thursday, October 4, 2018 in HART, News, Student/Alumni, VRC.

This blog entry, and another to follow, are among the final products of my on-site research this summer in the south of France, which was made possible by the generous support of a Downing Grant. As a History of Art graduate student at Vanderbilt, I spent three weeks conducting research between Marseille and Monaco, focusing primarily on Aix-en-Provence, Nîmes, Hyères, Antibes, Nice, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, Saint-Paul de Vence, and Roquebrune-Cap-Martin while exploring the region’s rich diversity of art and architecture. More than a travelogue, these posts offer an art historical approach to a variety of monuments based on close examination and analysis. My individual entries revolve around themes found throughout southern France such as multiculturalism and the impact of the environment on artistic creation, religion, and the lingering influence of the region’s classical past. This post addresses the first two themes.

This blog entry, and another to follow, are among the final products of my on-site research this summer in the south of France, which was made possible by the generous support of a Downing Grant. As a History of Art graduate student at Vanderbilt, I spent three weeks conducting research between Marseille and Monaco, focusing primarily on Aix-en-Provence, Nîmes, Hyères, Antibes, Nice, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, Saint-Paul de Vence, and Roquebrune-Cap-Martin while exploring the region’s rich diversity of art and architecture. More than a travelogue, these posts offer an art historical approach to a variety of monuments based on close examination and analysis. My individual entries revolve around themes found throughout southern France such as multiculturalism and the impact of the environment on artistic creation, religion, and the lingering influence of the region’s classical past. This post addresses the first two themes.

Multiculturalism in the South of France

The blending of diverse cultures quickly emerged as a powerful theme in my research in Provence and the Côte d’Azur, beginning with my visit to the Musée d’Histoire de Marseille. Marseille (ancient Massalia) was founded ca. 600 BCE as a colony of Greek Phocaea, Asia Minor (modern Foça, Turkey). Ancient sources boil this down to a story that the city arose from the marriage of a Gallic princess (Gyptis) to a Phocaean sailor (Protis). The legend of Gyptis and Protis allegorizes the foundation of the city and epitomizes the cultural exchange between the Greeks of Ionia and the Gauls of Provence. The founding myth lays the groundwork for the multiculturalism that defines the past, present, and future of Marseille. As a port city and thus a trade center from the 6th century BCE to the present day, Marseille has long been the major regional locus for exchange of

The blending of diverse cultures quickly emerged as a powerful theme in my research in Provence and the Côte d’Azur, beginning with my visit to the Musée d’Histoire de Marseille. Marseille (ancient Massalia) was founded ca. 600 BCE as a colony of Greek Phocaea, Asia Minor (modern Foça, Turkey). Ancient sources boil this down to a story that the city arose from the marriage of a Gallic princess (Gyptis) to a Phocaean sailor (Protis). The legend of Gyptis and Protis allegorizes the foundation of the city and epitomizes the cultural exchange between the Greeks of Ionia and the Gauls of Provence. The founding myth lays the groundwork for the multiculturalism that defines the past, present, and future of Marseille. As a port city and thus a trade center from the 6th century BCE to the present day, Marseille has long been the major regional locus for exchange of  Mediterranean products, philosophies and cultures—from the Greek, then Roman, to the French, and between France and the modern world. The Musée d’Histoire de Marseille emphasizes this theme in its curatorial perspective, highlighting objects that serve as testaments to the city’s origins of multiculturalism. For example, the collection of amphorae from the 6th and 5th centuries BCE reflect the amazing breadth of cultures that traded with ancient Massalia—from North Africa, Italy, and the eastern Mediterranean to Spain and Portugal.

Mediterranean products, philosophies and cultures—from the Greek, then Roman, to the French, and between France and the modern world. The Musée d’Histoire de Marseille emphasizes this theme in its curatorial perspective, highlighting objects that serve as testaments to the city’s origins of multiculturalism. For example, the collection of amphorae from the 6th and 5th centuries BCE reflect the amazing breadth of cultures that traded with ancient Massalia—from North Africa, Italy, and the eastern Mediterranean to Spain and Portugal.

I turn to one of the major modern monuments in the city: The Cathédrale Sainte-Marie-Majeure de Marseille (or Cathédrale de la Major) designed by Léon Vaudoyer alongside Henri Espérandieu, director of construction, and built between 1845 and 1893, reflects the city’s multiculturalism by embracing many cultures and artistic eras  in its unique architectural style. The cathedral has a medieval pilgrimage plan, classical domes, Middle Eastern minarets inspired by Islamic art and Moorish stone polychromy. In addition to reflecting the diversity of the city, the cathedral sits on a platform above the harbor. This position reflects the significance of Marseille as a port city, while connecting the metaphor found in the architecture to the port bringing together many cultures.

in its unique architectural style. The cathedral has a medieval pilgrimage plan, classical domes, Middle Eastern minarets inspired by Islamic art and Moorish stone polychromy. In addition to reflecting the diversity of the city, the cathedral sits on a platform above the harbor. This position reflects the significance of Marseille as a port city, while connecting the metaphor found in the architecture to the port bringing together many cultures.

The mayor of Marseille, Jean-Claude Gaudin, reflects upon the significance of the city’s history as a port and the peaceful intermingling of various cultures there: “It’s a port and so we have always been used to having foreigners come here,” he says in an interview with National Geographic. Marseille’s current culture of respect and inclusivity reflects and affirms the city’s multicultural mythology and history.

One of the most compelling instances of cultural exchange is in Saint-Paul de  Vence at the Fondation Maeght. The exhibition there in the summer of 2018, Lee Bae: Plus de Lumière, showcases Bae’s work with charcoal, including canvases of abstract charcoal script and monumental sculptures of stacked charcoal, a traditional material from his native country of South Korea. His decision to bring his monumental works to the Fondation Maeght was largely inspired by his interest in the encounters between different cultures. Describing Issu de feu (2000), a sculpture composed of charcoal trunks tied with elastic threads, he shares the process and his philosophical approach: “I had the bundles sent from Cheongo, where I was born, near Daegu, in South Korea. I had them made in Korea; I brought them here as an encounter between the pines of Saint Paul and Korean pines. I like this idea of displacement, of travel, which corresponds to my way of thinking and what has been my way of life for going on thirty years, what with my regular journeys back and forth between France and my country of origin.”

Vence at the Fondation Maeght. The exhibition there in the summer of 2018, Lee Bae: Plus de Lumière, showcases Bae’s work with charcoal, including canvases of abstract charcoal script and monumental sculptures of stacked charcoal, a traditional material from his native country of South Korea. His decision to bring his monumental works to the Fondation Maeght was largely inspired by his interest in the encounters between different cultures. Describing Issu de feu (2000), a sculpture composed of charcoal trunks tied with elastic threads, he shares the process and his philosophical approach: “I had the bundles sent from Cheongo, where I was born, near Daegu, in South Korea. I had them made in Korea; I brought them here as an encounter between the pines of Saint Paul and Korean pines. I like this idea of displacement, of travel, which corresponds to my way of thinking and what has been my way of life for going on thirty years, what with my regular journeys back and forth between France and my country of origin.”

The idea of traveling between cultures also can be observed in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat at Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild, the seaside mansion of Baroness Béatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild. The magnificent garden, designed by Achille Duchêne between 1905 and 1912, is divided into nine parts, many of which reflect different cultures ranging from Florentine to Spanish to Japanese to Provençal to French. This design enables one to move from one culture to the next, acting as a microcosm of an extensive cultural journey throughout the world and reflecting the experience of traveling throughout the culturally diverse Provence-Côte d’Azur region.

The idea of traveling between cultures also can be observed in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat at Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild, the seaside mansion of Baroness Béatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild. The magnificent garden, designed by Achille Duchêne between 1905 and 1912, is divided into nine parts, many of which reflect different cultures ranging from Florentine to Spanish to Japanese to Provençal to French. This design enables one to move from one culture to the next, acting as a microcosm of an extensive cultural journey throughout the world and reflecting the experience of traveling throughout the culturally diverse Provence-Côte d’Azur region.

The Impact of the Environment on Artistic Creation in the South of France

The natural splendor of the region exerts a strong influence on art and architecture. By way of illustration, Montagne Sainte-Victoire in Aix-en-Provence inspired a series of paintings by Paul Cézanne, who was born in Aix and resided there for the majority of his life until his death in 1906. And of course, many will know of Vincent Van Gogh’s love of the region, specifically the town of Arles, although I did not have the opportunity to visit Fondation Vincent Van Gogh Arles. Finally, at Nice, the sea inspired Henri Matisse to stay and create the majority of his works there. In addition to inspiring paintings, the landscape of the South of France also plays a major role in shaping architecture.

Architect Eileen Gray’s E1027 (1926-1929) in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin serves as a powerful example of the environment’s impact on architecture. The villa is perched on a rocky cliffside overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. The minimalist, whitewashed exterior of the home and the flat roof ensure that the architecture complements the natural surroundings. A long terrace stretches across the house, emphasizing the vista. The house can only be entered in groups organized at the Cap Moderne visitor center, and on my visit, the official guide memorably stated that the true luxury of the home was the view, in response to a comment about the villa’s minimalism. Gray’s design positions the viewer to experience the vista throughout the villa, as one even has a great view from the bathroom!

Architect Eileen Gray’s E1027 (1926-1929) in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin serves as a powerful example of the environment’s impact on architecture. The villa is perched on a rocky cliffside overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. The minimalist, whitewashed exterior of the home and the flat roof ensure that the architecture complements the natural surroundings. A long terrace stretches across the house, emphasizing the vista. The house can only be entered in groups organized at the Cap Moderne visitor center, and on my visit, the official guide memorably stated that the true luxury of the home was the view, in response to a comment about the villa’s minimalism. Gray’s design positions the viewer to experience the vista throughout the villa, as one even has a great view from the bathroom!

Nature further influences the architecture, as the villa is oriented to maximize sunlight: “the bedrooms face east to take advantage of the morning sun, and the  main living area faces full south towards the sea for natural light throughout the day” (Cap Moderne Museum). Nature seeps deeper into the villa, as the four dominant colors are borrowed from the surroundings: green, red, blue and white. The villa also features a blossoming garden, which is emphasized through the leisurely approach towards the entrance to the villa.

main living area faces full south towards the sea for natural light throughout the day” (Cap Moderne Museum). Nature seeps deeper into the villa, as the four dominant colors are borrowed from the surroundings: green, red, blue and white. The villa also features a blossoming garden, which is emphasized through the leisurely approach towards the entrance to the villa.

The water inspires another aspect, the villa’s nautical theme. E1027 mimics a boat floating above the water, as pointed out in the nearby museum: The terrace  emulates a ship’s deck, complete with “canvas covered railings and lifebuoys” and its staircase acts as an anchor. In the main room, a map of the Caribbean with the words “Invitation au Voyage” represents both the nautical theme and the book and poem by Charles Baudelaire of the same title from 1857. The furniture is mostly blue and white, featuring nautical stripes. According to the Cap Moderne Museum, the name of the home even stems from maritime registration numbers, although some believe the number is a clever combination of Gray’s name and the name of her lover and fellow architect, Jean Badovici, for whom she built the villa. Notwithstanding, E1027 clearly pays homage to the sea through its emphasis on vistas, incorporation of elements from the surrounding landscape, and the maritime theme.

emulates a ship’s deck, complete with “canvas covered railings and lifebuoys” and its staircase acts as an anchor. In the main room, a map of the Caribbean with the words “Invitation au Voyage” represents both the nautical theme and the book and poem by Charles Baudelaire of the same title from 1857. The furniture is mostly blue and white, featuring nautical stripes. According to the Cap Moderne Museum, the name of the home even stems from maritime registration numbers, although some believe the number is a clever combination of Gray’s name and the name of her lover and fellow architect, Jean Badovici, for whom she built the villa. Notwithstanding, E1027 clearly pays homage to the sea through its emphasis on vistas, incorporation of elements from the surrounding landscape, and the maritime theme.

Across the entire region, the natural beauty of the land and sea has sparked an interest in preserving the environment. The collection at Château La Coste reflects an environmentalist philosophy througho ut the vineyard and outdoor art center. The Art and Architecture Walk highlights the property’s large-scale installations by such esteemed artists and architects as Louise Bourgeois, Alexander Calder, Richard Serra, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, and Tadao Ando. Five of Ando’s works are featured on the Art and Architecture Walk, including Pavilion, Four Cubes to Contemplate our Environment (2008-2011). The glass installation consists of four cubes that work together to serve as a call to action; the artist intends for this work to inspire environmentalism: “I would like people to think of what they could do to improve things when they look into the box” (Château La Coste Art and Architecture Walk). The first three cubes are marked with repeating labels, such as “CO2,” “WATER,” and “RUBBISH” and feature items inside reflecting their respective labels.

ut the vineyard and outdoor art center. The Art and Architecture Walk highlights the property’s large-scale installations by such esteemed artists and architects as Louise Bourgeois, Alexander Calder, Richard Serra, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, and Tadao Ando. Five of Ando’s works are featured on the Art and Architecture Walk, including Pavilion, Four Cubes to Contemplate our Environment (2008-2011). The glass installation consists of four cubes that work together to serve as a call to action; the artist intends for this work to inspire environmentalism: “I would like people to think of what they could do to improve things when they look into the box” (Château La Coste Art and Architecture Walk). The first three cubes are marked with repeating labels, such as “CO2,” “WATER,” and “RUBBISH” and feature items inside reflecting their respective labels.

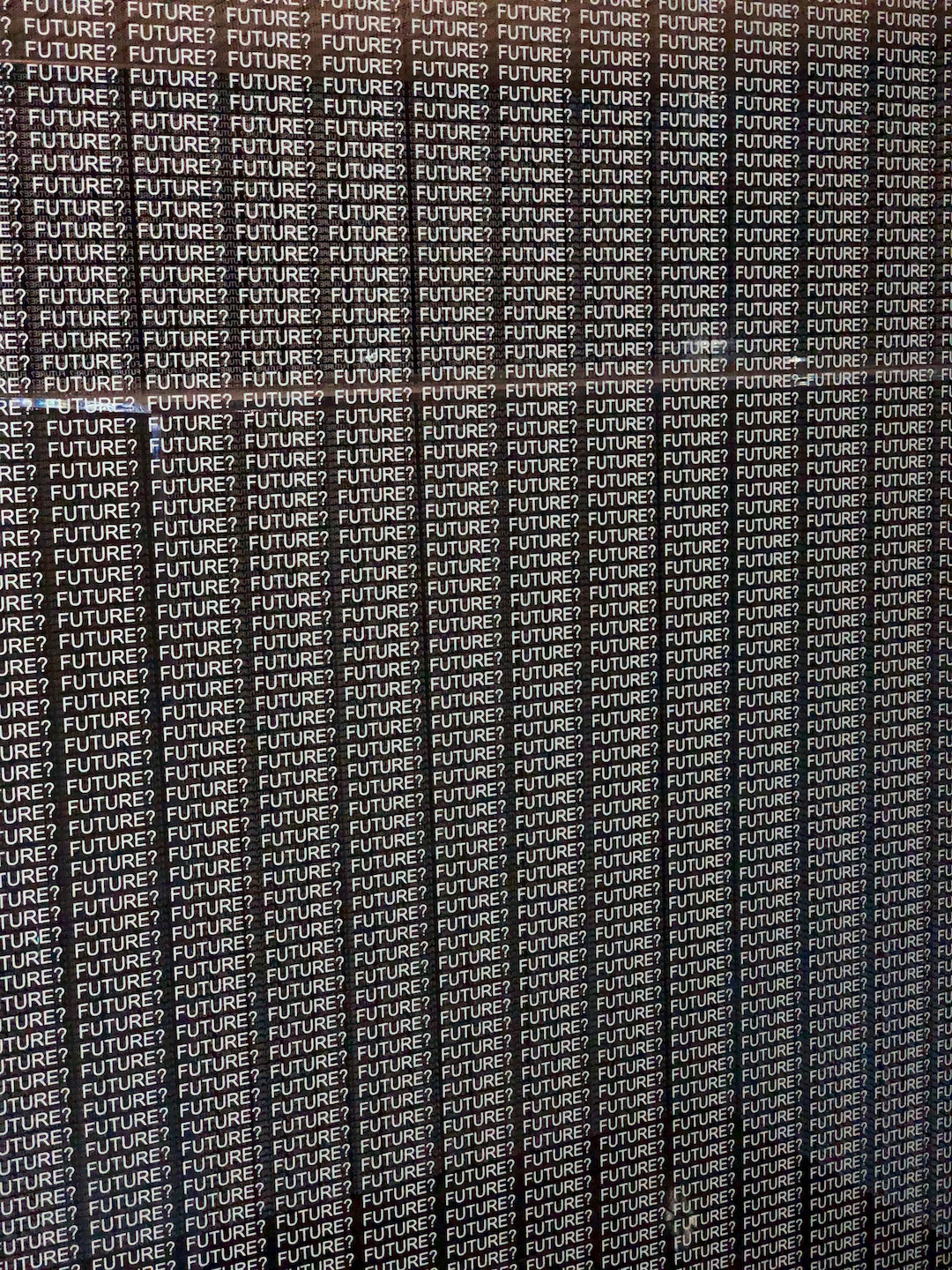

The fourth cube is especially poignant, as the word “FUTURE?” repeats against an empty cube. I was reminded of this question, “FUTURE?” when I saw Monaco’s oil rigs and the pollution that abound in Marseille’s Vieux Port, and also when I saw the Mediterranean Sea from E1027 and the cliffs of Montagne Sainte-Victoire from the Bibemus Quarry nearby. Such juxtapositions serve as reminders that these pockets of natural splendor need our protection, now more than ever.

The fourth cube is especially poignant, as the word “FUTURE?” repeats against an empty cube. I was reminded of this question, “FUTURE?” when I saw Monaco’s oil rigs and the pollution that abound in Marseille’s Vieux Port, and also when I saw the Mediterranean Sea from E1027 and the cliffs of Montagne Sainte-Victoire from the Bibemus Quarry nearby. Such juxtapositions serve as reminders that these pockets of natural splendor need our protection, now more than ever.

©2026 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications