Home » HART » Review of Camille Utterback’s Exhibit at the Frist through May 19

Review of Camille Utterback’s Exhibit at the Frist through May 19

Posted by vrcvanderbilt on Monday, April 15, 2013 in HART, Student/Alumni, VRC.

Camille Utterback’s exhibit, Tracing Time/Marking Movement, at The Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee, offers a divergence from the typical museum visit; it allows each visitor to be both viewer and participant. The exhibition, on view through May 19, features seven works of art, four of which require interactivity.

Camille Utterback’s exhibit, Tracing Time/Marking Movement, at The Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee, offers a divergence from the typical museum visit; it allows each visitor to be both viewer and participant. The exhibition, on view through May 19, features seven works of art, four of which require interactivity.

The first work that the viewer sees is Liquid Time—Tokyo (image 1). On initial glance, this work looks like an enlarged photograph, but as one moves toward the lighted square on the ground, the image begins to adjust, and the figures on the screen appear to move. The movements of the people in Tokyo directly correlate with the movements of the viewer in front of the screen. In Utterback’s demonstration, she revealed how the positioning of motion is crucial. She instructed a child to tap the floor on the lit area closest to the image. In doing so, a fragment of the image returned to the beginning of the frame, showing the figures as they walked toward their initial resting place. The size and contours of the viewer’s body reflect the degree to which the image adjusts. Through play and exploration, the viewer can experience the full potential of the effect of one’s body on the image.

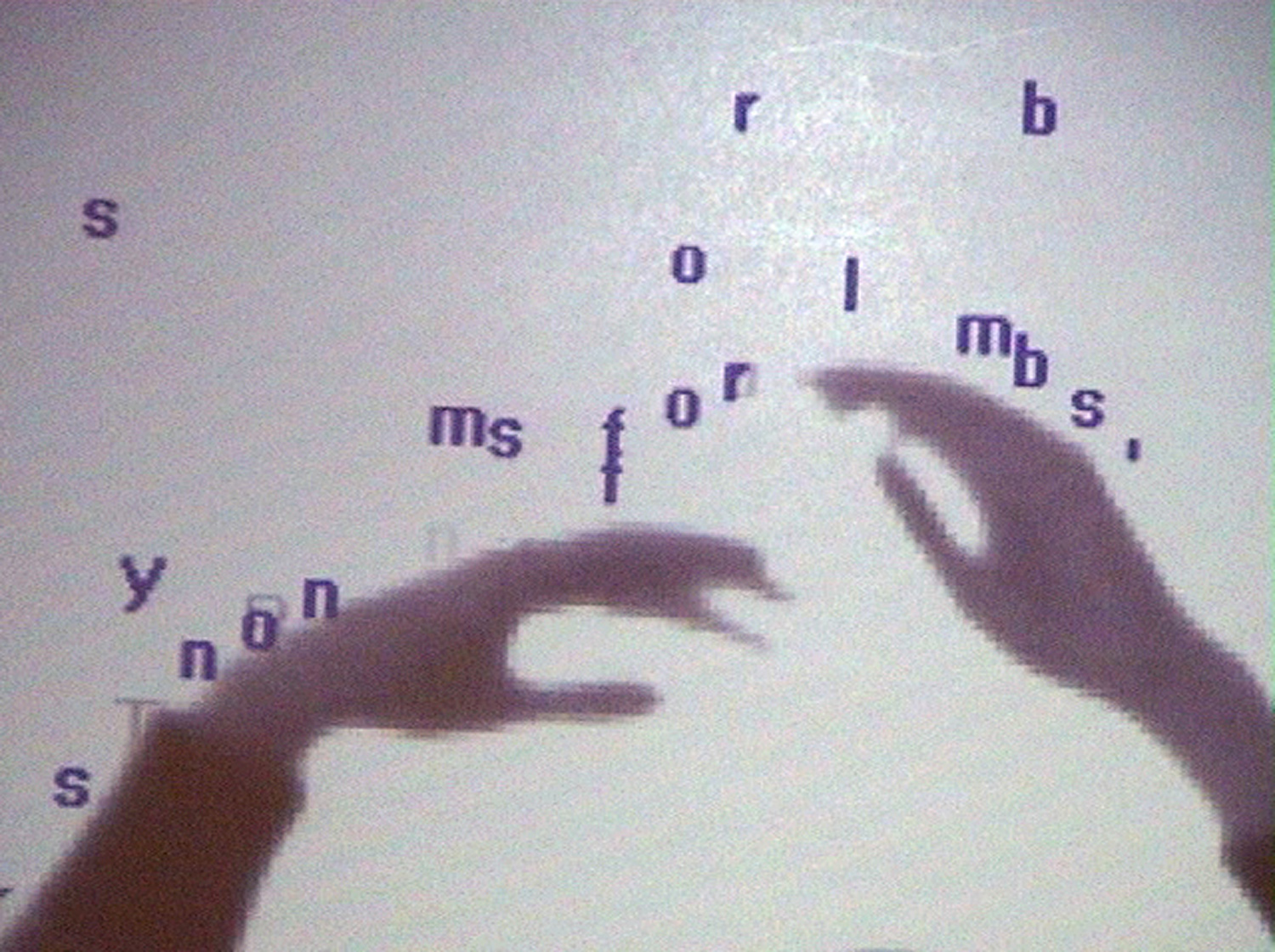

This same concept of learning through interaction is further realized as one moves into the next room. Text Rain (image 2) projects the viewer’s body onto the screen. Letters fall onto the outline of the viewer’s shape. Lighter colored letters disappear as they fall down, while the letters with darker hues easily keep floating. With Text Rain, Utterback challenges previous conceptions of the use of words by adding a physical element. Robert Simanowski notes, “The letters are liberated from their representational function. They have left language behind and turned into visual objects as part of an interactive installation.” (Digital Anthropophagy, 159).

This same concept of learning through interaction is further realized as one moves into the next room. Text Rain (image 2) projects the viewer’s body onto the screen. Letters fall onto the outline of the viewer’s shape. Lighter colored letters disappear as they fall down, while the letters with darker hues easily keep floating. With Text Rain, Utterback challenges previous conceptions of the use of words by adding a physical element. Robert Simanowski notes, “The letters are liberated from their representational function. They have left language behind and turned into visual objects as part of an interactive installation.” (Digital Anthropophagy, 159).

In the room to the right of the central room, large projections of color reveal themselves to the visitor. These are Utterback’s most recent installations, Untitled 5 and Untitled 4 (image 3). Marianne Adams describes the experience as follows: “Simply by moving or gesturing in the space in front of these images, participants can change them, altering their colors, patterns, and shapes.” (The Dilemma of Interactive Art Museum Spaces, 46).  As the quotation suggests, Untitled 5 and Untitled 4 differ from Text Rain and Liquid Time—Tokyo in that movement does not fragment a stable image but creates new images. By waving an arm, color is splattered on the surface. By picking up a foot, that movement is then washed over with more color of a different palette.

As the quotation suggests, Untitled 5 and Untitled 4 differ from Text Rain and Liquid Time—Tokyo in that movement does not fragment a stable image but creates new images. By waving an arm, color is splattered on the surface. By picking up a foot, that movement is then washed over with more color of a different palette.

In these two installations, it becomes clear that the viewer is the artist. Nathaniel Stern suggests, “Her installations are not objects to be perceived but relations to be performed.” (The Implicit Body as Performance, 233). As Stern proposes, the artist is now not the only factor in control of the work of art. In effect, this installation allows for every viewer to be the artist. The visitors not only get to see art, but create it.

Three other works hang on the walls of the third room. They consist of altering shapes, forms, and colors. However, despite their mutating states, these works do not suit the rest of the exhibit. Their small size stands in stark contrast with the enormous interactive installations. Additionally, their lack of interactivity is confusing to the visitor. After enjoying four interactive images, one becomes accustomed to the expectation of interactivity. Discovering that these last three works do not require participation is a disappointment. They clutter the gallery space, rather than enhance it.

Despite these failings, the exhibition is entertaining. Through the setup of the exhibition and subsequent installations, the viewer is encouraged to explore his body motions and see the effects displayed before him. Utterback’s exhibit invokes curiosity and a desire to learn more. Yet, she achieves this desire by giving each viewer a novel experience. No two visitors will see the same images. More than that, this exhibit allows the viewer to share the artistic creativity with the artist. No longer is the work of art solely a creation of the artist; it is a result of the participant, too. While playing with her exhibitions, it is hard not to raise questions about what art really is and what one’s relation to it should be. In this regard, Utterback’s exhibit is successful because it questions the traditional view of the artist and one’s own conception of art.—Robyn Christine Taylor

Works Cited:

Adams, Marianna, Cynthia Moreno, et al. “The Dilemma of Interactive Art Museum Spaces.” Art Education. 56.5. Print.

Simanowski, Roberto. “Digital Anthropophagy: Refashioning Words as Image, Sound and Action.” Leonardo. 43.2 Print.

Stern, Nathaniel. “The Implicit Body as Performance: Analyzing Interactive Art.” Leonardo. 44.3. Print.

Image 1: Camille Utterback. Liquid Time—Tokyo (screen detail), 2001. Interactive installation; custom software, video camera, computer, projector, and lighting. Courtesy of the artist.

Image 2: Camille Utterback and Romy Achituv. Text Rain (screen detail), 1999. Interactive installation; custom software, video camera, computer, projector, and lighting. Courtesy of the artists.

Image 3: Camille Utterback. Untitled 5 (installation view), 2004. Interactive installation; custom software, video camera, computer, projector, and lighting. Courtesy of the artist. Photography by Tom Bamberger.

©2026 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications