On my last unrestricted blog post, I began a series of posts on my favorite topic in astronomy: The Voyager Golden Record. If you missed that blog post you can check it out here. Basically, the golden record is a message in a bottle being cast into the cosmic ocean. It will go very far away and will last for a very long time. In the unlikely circumstance that other intelligent life finds the record, they should be able to discover the message within: a series of images and sounds that are a representation of humanity and life on Earth.

The next unrestricted blog post will cover the actual content of the record, which is fascinating. For this blog I will be explaining the instructions on how to read the record. Most people think that reading the instructions is boring, but in this case it is actually amazing.

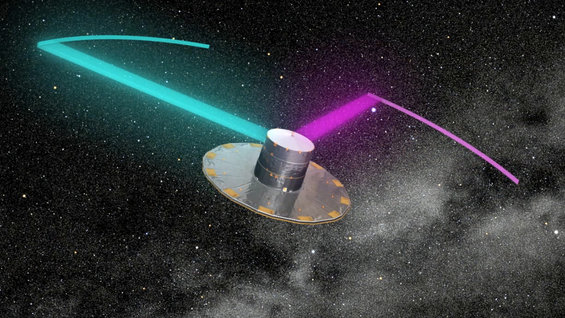

To start off, you have to wrap your head around this concept: if another intelligent life were to ever find the voyager golden record, we would be the aliens to them and our technology would be alien. With that in mind, how do we explain how to listen to a record machine? How can we transfer all this audio and picture data to a completely unknown form of life that almost certainly doesn’t have eyes or ears like we do?

Well here is how they did it: check out the cover of the record. The cover has the instructions on how to play the record in eight symbols which I will now explain.

Starting in the bottom right, there are two circles. These represent the two fundamental states of the hydrogen atom. The energy transition of electrons between these two states takes a certain amount of time which will be consistent all over the universe. This is what they are defining as 1 t, the standard unit of time.

Next move to the top left, where you can see a top down view of the record and its stylus. There is also binary code around the edge of the record. The binary code is defining the proper rotational frequency of the record in the hydrogen unit of time that was previously defined. In seconds, this frequency is 3.6 seconds per rotation.

Below this image is a side view of the record and stylus with more binary code beneath it. This binary code is telling the user the total amount of time that the record should take, again defined in the fundamental transition of hydrogen time. In our time, the record will finish in about an hour. The position of the stylus indicates that the record should be played from the outside in.

Ignore the star looking thing in the bottom left for now and move to the top right. Things get a bit more complicated here. The basic way that a record works is that there is a spiral groove going from the outside to the inside. Inside this spiral groove is a waveform that the stylus will trace and read as it moves up and down very slightly. This waveform is what’s being shown in the top right. The first, second, and third waveforms are indicated above by binary code. Below is binary code with the approximate time to scan one of these waveforms, which is about 8 milliseconds.

Next, the image is made up of these waveforms. The waveforms are actually vertical lines that make up image. The binary code above the rectangle with all the jagged vertical lines says that a complete image is made with 512 vertical lines. Below this is a rectangle with a circle in it. The first image on the golden record is a simple, perfect circle. The circle was used so that the horizontal and vertical aspect ratios are correct. If the receiver of the disk sees a circle as the first decoded image, they will know that they are seeing it right.

Now this may seem like a really difficult set of instructions to follow, but you have to remember that any intelligent life that theoretically found the Voyager would be capable of interstellar travel. This means that they would almost certainly be able to reverse-engineer a record player with the instructions that were provided.

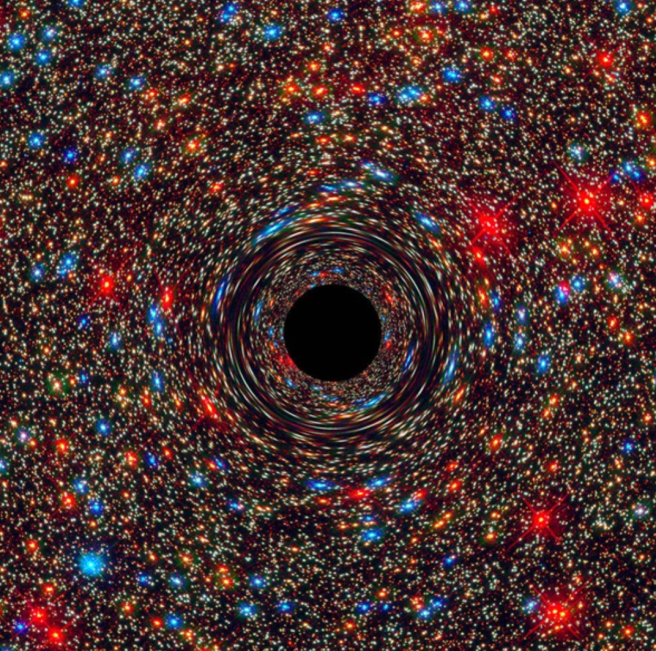

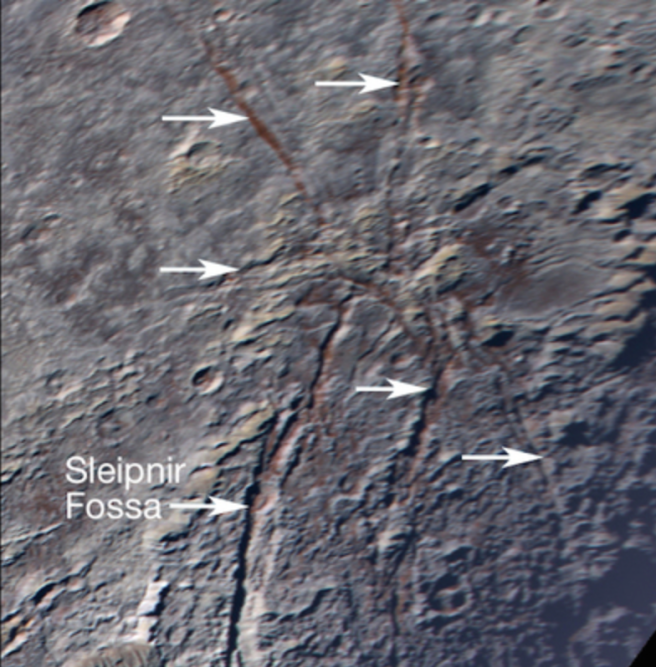

Finally, the image in the bottom left is actually a map. This image shows our sun’s location in relation to 14 pulsars. Pulsars are stars that pulse at a steady and consistent frequency. The lines extending from the center to the pulsars have binary code along them that list the frequency of the pulses. Pulsars are good cosmic landmarks because they’re very obvious and easy to find.

Pretty cool, right? Who knew reading the instructions could be so interesting? Next time I’ll get to the actual content on the Golden Record. It’s awesome, get excited. Again, if you read this and don’t want to wait, check it out here.

Explanation Source