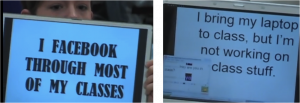

A recent study on students’ laptop use in the classroom has brought a lot of attention to the issue of, well, attention in the classroom. As their title indicates, Sana, Weston, and Cepeda (2013) found that “Laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers.” In a 45-minute lecture, half the students were given 12 questions easily answered by Google searches and the like (e.g., “What is on Channel 3 tonight at 10 pm?”), simulating the kinds of activities students might do while listening to a lecture. In the comprehension test immediately following the lecture, those who multitasked on their laptops scored 11% lower than those who didn’t, and even more significantly, students not using laptops but in view of one scored 17% lower (p. 27, 29).*

I’ve long preferred no laptops in the classroom because I want my students fully present, engaging with the text and actively listening to and frequently looking at each other as they talk. I’m sure some students can juggle all of these tasks to some degree, but I’d prefer to keep it simple, help students resist temptation, and ultimately protect the concentration of the whole class. Sana and colleagues validate the concern about laptops in the classroom as more than a Luddite’s backlash; in fact, it’s worse than we expected in this effect on the other students.

So to help our students be fully present–engaged and attentive to their classmates, to us, to their texts and other class materials–during our short time together, we can have them not use their laptops when not doing computer-based learning activities, but what can we have them do?

One simple, easy option is embracing silence. In last week’s Chronicle, Charlie Wesley made a case for silence in the classroom: “Silence and speech exist together in a symbiotic relationship. Silence is not merely the antithesis of speech but rather the necessary precondition for authentic, lively, and engaged speech.” He pointed out that assigning such pauses can help “relieve [the] anxiety” of naturally quieter students and manage the “overambitious student [who] will seek to fill the silence.” These moments give students time to “genuinely mull over something” and to “form a more authentic and considered response.”

After lunchtime yoga a few weeks ago, my colleague Trudy Stringer shared with me a classroom practice she uses to bring students fully present, and she gave me permission to share it here.

Practice

-

When class begins, tell your students you’d like everyone to fully arrive, including yourself.

-

Ask them to identify one thing they’ve brought to class–a thought, an experience, a worry, a joy, or a burden–they’d like to leave at the door, just for this short class period together, to be fully present.

-

Make time for them (and for yourself) to name it: to simply imagine getting up and leaving it at the door, or to write it down and fold the paper in half or put it under their desks. A moment of silence will facilitate this psychic shift into the room for those who are willing (and won’t harm those who resist).

-

At the end of class, acknowledge and thank them for their focused presence, and encourage them to reflect on this experience in class compared with others.

This practice makes me think of swaddling babies to calm them down, Thundershirts for dogs afraid of storms, Temple Grandin’s “hug machine” to soothe her (and later cattle) in stressful situations, and even our complaints-that-turn-to-relief when we have no cell phone reception. Initial reactions of resistance or struggle give way to surrendering to the moment, perhaps even pleasure, and we soon become grateful for the imposed stillness.

This reminds me of Richard Felder’s argument that some students prefer active learning (discussing material with others), some prefer reflective learning (thinking to oneself about material), and the traditional college lecture, with its steady stream of words from the instructor, makes little room for either form of learning!

Just because no one is talking, doesn’t mean that no one is thinking…