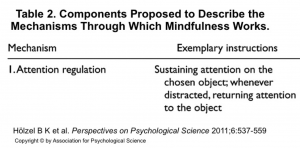

My recent posts have been focused on issues of stress, mostly because I’ve seen the effects on my own life and worry about colleagues, students, and friends. Some of you have asked me to clarify how mindfulness works: what it actually does, how that happens, and what it looks like. With these great questions in mind, I’ll devote the next few posts to addressing “How It Works” in more depth, one “mechanism” at a time (Hölzel et al, 2011). This week: attention regulation.

Click to enlarge this excerpt. Stay tuned for posts about the remaining 3 components (Hölzel et al, 2011, p. 539).

Attention regulation means focus. It’s the foundation of the practice of mindfulness–and improved attention regulation is also a consequence. In the practice, we focus on a single object, idea, or sensation. When our minds wander off–as they do–we simply bring our attention back to that focus. That’s it. That’s the practice. As our minds wander and we start to think about grading or meetings or To Do lists, we simply notice the wandering and bring our attention back to that focus. Surprisingly, this wandering is not a problem, a fault, or a failure. Think of it as hills for a runner: this recognition of “my mind has wandered” and then redirection back to the focus is a key part of the workout that strengthens our ability to regulate our attention in other situations.

What’s happening in the brain that facilitates this improvement? Functional MRIs have shown that this practice activates and strengthens the function of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which monitors and regulates distraction–or “conflicts emerging from incompatible streams of information processing” (Hözel et al, 2011, p. 540). What is the brain then able to do? The skills, documented through both self-reports and empirical measures in multiple studies, are described as

- increased “‘orienting’ (directing and limiting attention to a subset of possible inputs),”

- improved “‘alerting’ (achieving and maintaining a vigilant state of preparedness),”

- decreased “attentional blink effect (a lapse in attention following a stimulus within a rapid stream of presented stimuli),” and

- greater control over “distribution of brain resources” (Hölzel et al, 2011, p. 541).

And it doesn’t require training-for-a-marathon practice: even just five days of practice has an effect, such as significantly decreased error scores on an Attention Network Test (Tang et al, 2007).

Consider the implications of getting better at regulating our attention. We can focus our attention for longer periods, we’re distracted from that focus less easily, and we recover from distraction more quickly. I’ve long struggled with these kinds of transitions, especially when I’m “in the zone,” so I’m particularly grateful for this workout. If a phone call interrupts us while we’re writing, we can pick up where we left off in the writing more easily. If we’re grading a stack of essays and need to stretch our legs, we can return to the grading more smoothly. If our minds or our students’ minds wander in class, we can rejoin what’s happening in the room more quickly. If someone interrupts a student while studying for an exam, it’s easier to get back to the deep thinking. For more about attention regulation and its specific relevance to us and our students, read my earlier post “Paying Attention” and its connection to metacognition.

Practice

This issue of attention regulation takes us back to an earlier practice described in “The Easy Way & the Easier Way“:

“The creatively named Easy Way is to simply bring gentle and consistent attention to your breath for two minutes. That’s it. Start by becoming aware that you are breathing, and then pay attention to the process of breathing. Every time your attention wanders away, just bring it back very gently.” (Tan, 2012, p. 26)

Here’s a timer. In “The Easy Way & The Easier Way” you did this for two minutes. Now, set it for 4:00 or 5:00. When you click “Start,” look down comfortably, or close your eyes. The timer will alert you at the end.

Remember, focus on your breathing. As your mind wanders, that’s okay. Just notice “wandering,” and then return to your breath. Wandering. Breath.

Next week, I’ll write “How It Works, II.” There will be four of these posts, and then I want to spend some time focusing on how students and their learning are affected by mindful practices.

—