This is the fourth and final post about how mindfulness works, or the documented effects and how they occur. The first was about attention regulation, the second body awareness, the third emotional regulation, and now a different perspective of the self.

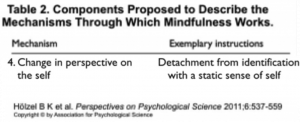

There are few silver bullets in teaching and learning, but a handful of strategies are so grounded in evidence that I sometimes feel like shouting from rooftops. One is metacognition.* Another is how students view their own intelligence. Carol Dweck describes it as having either a “fixed mindset” (believing that intelligence is “inborn,” unchangeable) or “growth mindset” (believing that intelligence can be developed, increased), each of which “leads to different school behaviors” (2010, p. 16). These mindsets are related to the equally compelling notion of “locus of control” (Fazey & Fazey, 2001), or what we believe about control in our life events. A student with an internal locus of control believes that she has control over what happens in her life, whereas one with an external locus of control believes that external factors are in control, and he is powerless. These mindsets also lead to different learning behaviors (“If I work hard, I can do it!” vs. “I just can’t do math because it’s too hard, so it’s not worth it to try” or “I failed the test because it was unfair, not because of how I studied.”). All three of these ideas–metacognition, fixed vs. growth mindset, internal vs. external locus of control–come to mind when I read about the final mindfulness “mechanism” described in Hölzel and colleagues’ meta-analysis of the scientific research: a “change in perspective of the self” (2011, p. 547-550).

More advanced practitioners of mindfulness report moving from a belief in a “static self” (“a constant and unchanging entity”) to an “‘experiencing'” self that is always changing, “transitory” (Hölzel et al., 2011, p. 547). Rooted in Buddhism, this shift called “‘reperceiving’ or ‘decentering'” is reported more frequently by those with lots of mindful practice, but its beginnings are reported by newbies as well. Self-report studies document the development of a “meta-perspective on experience” after mindfulness practice, and neuroimaging shows structural changes (increased gray matter) in the parts of the brain responsible for “the experience of the self” and “remembering the past, thinking about the future…, and conceiving the viewpoint of others, also referred to as a theory of mind” (p. 549). While these changes are “precisely described in the Buddhist literature,” Hölzel and colleagues are quick to point out that this effect has the fewest studies of the four mechanisms, so they caution that it hasn’t yet been “rigorously tested in empirical research.”**

Nevertheless, an increasing meta-awareness of the self as something that’s always changing and can be changed is so intertwined with the previous mechanisms (attention regulation, body awareness, and emotional regulation) that Hölzel and colleagues include it in their list that synthesizes “the existing literature into a comprehensive theoretical framework” (p. 537). They explain this “integration” by which the four “components mutually facilitate each other” in the lengthy but effective excerpt to the right. (Click it and read it, really!) It helped me understand more fully how mindfulness is not just about being aware. This awareness facilitates intentional changes in thinking habits, rewiring the brain to create new, more effective mental habits, which then affect physiological and mental health.

…and, as I’ll focus on more in the coming weeks, these processes also affect learning.

Practice

- Sit comfortably in your chair, hands in your lap, back straight but relaxed.

- Take a slow, deep breath.

- Notice what the floor feels like under your feet. Notice what your chair feels like under your seat. Notice what your hands feel like in your lap. Notice what your head feels like above your shoulders.

- At once, notice the feeling under your feet and the feeling of your head above your shoulders. Stay there with this first-person perspective on your entire body.

- Take a slow, deep breath.

- Now, bring your awareness to the edges of the room where you sit, and picture yourself sitting as you are. See yourself from this “fly-on-the-wall” perspective. Notice the floor under your feet, the chair you sit in, your hands in your lap, and your head held by your neck. Pause and stay with this attention to your entire body–from a third-person perspective.

- Repeat the above shifting from an internal to an external perspective on your body, the most obvious expression of your self.

- Breathe.

—

* See my previous post connecting mindfulness to metacognition, and see my metacognition guide for how to bring it into your classes.

** One reason for this relative lack of research may be the relatively limited access to expert practitioners. This mechanism is most pronounced in experts, but many (most?) studies are conducted on people newly introduced to mindfulness–to demonstrate a before-after change.

—