I recently announced on Facebook that I take requests. My friend and former colleague Marnie Bullock Dresser asked the following question:

“I can already tell there are fewer monkeys when I’m in serious monkey mind mode. I can tell my brain is different; I’m just wanting to trust that I’m making permanent changes–so that’s a request. Long term, maintained change–how likely?“

What a great question, similar to what we ask about our teaching. Students may dazzle us during the semester and on the final exam, but what about months later? A year later? Beyond that? Does the learning last?

Most of the mindfulness studies I’ve read measure the immediate effects of a specific experience, most often an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) class. More recent studies have added an additional follow-up assessment ranging from a few months to two years after the class (e.g., Anderson et al. [2013] followed up after 6 and then 12 months; Davidson et al. [2003], 4 months; Fortney et al. [2013], 8 weeks and 9 months; Gonzalez-Garcia et al. [2013], 20 weeks; Henderson et al. [2013], 4 months and 2 years; Roeser et al. [2013], 3 months; Tan & Martin [2012], 3 months; Weijer-Bergsma et al. [2012], 7 weeks). If there are studies that look at the impact beyond two years, I haven’t come across them yet.* (If you know of any, please let me know!)

Generally, these studies have found that many of the psychological effects are maintained during this time period. Even further, in their study of long-term HIV-positive patients, Gonzalez-Garcia et al. (2013) found positive psychological and physiological effects over time. In fact, both actually improved between the immediate post-tests after the 8-week class and the 20-week follow-up (i.e., reduced anxiety, stress, depression with scores like 25 at baseline, 10 at 8 weeks, and 7 at 20 weeks; increased CD4 immune cell counts from 555 cells/mL to 614 to 681). In contrast, the control group’s psychological scores were unchanged during this time, and their immune cell counts declined. I also just read an article coming out next month that documents changes in the expression of the genes associated with decreasing inflammation, reducing pain, and lowering the stress hormone cortisol after stressful events (Kaliman, 2014). What’s more, these effects occurred after a single, eight-hour day of intense mindful practice. Changes in gene expression? Maybe it’s the literary-scholar-who-loves-a-metaphor in me, but that strikes me as a profoundly “long-lasting” change.

What about measurements of our students’ learning over time? Institutional research and assessment offices may do such longitudinal retention and impact studies, but we instructors rarely conduct our own class- or discipline-specific follow-ups, and we’re often unaware of these institutional studies, or they’re fairly generic related to what we teach. We cherish our anecdotal examples of impact, though. I will always keep my copy of Yann Martel’s Life of Pi gifted to me by a former student, who inscribed the book with the most wonderful note about her love of reading since my literature class years ago. And I’m so grateful to have kept in touch with a women’s studies student from long ago, because I know that she went on to earn a degree in legal studies and is now a domestic violence victim advocate.

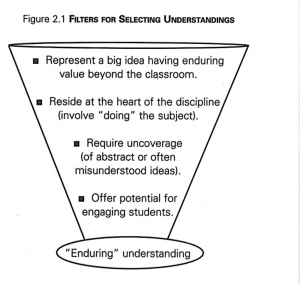

Ultimately, we’re wondering about what Wiggins and McTighe (1998) call “enduring understandings” (p. 10), characterized by the qualities in the graphic to the right. I think about them as what I want students to remember, do, and value five years after the class has ended. Wiggins and McTighe encourage course design with enduring understandings as the goal, not simply performances on tests and papers. Because the planning begins with the end goals in mind, this well-known course development process is called “backward design” (p. 23).

What are the enduring understandings for your classes? How do you communicate them? How do your students practice them?

Practice

When I think of this notion of enduring understandings, the image in my mind is a tree, especially the layers of meaning and memory embedded in concentric circles deep inside. Trees are also all around us (to some degree, depending on context), keeping us company, though rarely in the forefront of our minds. This week’s practice will be tree-centric. If you can see a tree, look at the tree. Otherwise, you’ll imagine a tree, a specific tree.

- Close your eyes, and take three slow, deep breaths to arrive here and now.

- Once your mind is calm and present, open your eyes and look at the tree. (If you’re imagining your tree, you may keep your eyes closed.)

- Now, breathe normally. Observe every detail of the tree.

- Pause and notice the light falling on the tree.

- Pause and notice the tree’s varied textures.

- Pause and notice the tree’s movements and/or stillness.

- Pause and picture the inside of the tree, the concentric circles of age and experience of this tree. Are there many? Pause and visualize them.

- How long might it have been here? Years? Decades? A century? Pause and experience that expanse of time.

- What physical sensations does this experience stimulate?

- Picture what it looked like as a sapling, and then as it grew to its current age and size. Pause and notice the tree as it is now. Pause here for as long as you’re comfortable.

- Take three slow, deep breaths, and bring your awareness back to your body, where it is, as it is.

—

* This is a good time for a disclaimer again that I am not a mindfulness expert or any kind of “-ist,” but I do enjoy reading these studies.

—