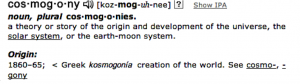

The progressive breakdown of my computer and resulting residencies of IT guys have conspired to force me to read some of the books I have stacked on my desk. Today, I read the copy of Teaching with Heart: Poetry that Speaks to the Courage to Teach (Intrator & Scribner, eds., 2014) we ordered for our library at the Center for Teaching. The book is a collection of poems selected and prefaced by educators who were called to submit poems that were meaningful to their work lives. A few stood out to me, but for today, I want to share a passage by Chuang Tzu (p. 155):

There was a man who was so disturbed by the sight of his own shadow and so displeased with his own footsteps that he determined to get rid of both. The method he hit upon was to run away from them.

So he got up and ran. But every time he put his foot down there was another step, while his shadow kept up with him without the slightest difficulty.

He attributed his failure to the fact that he was not running fast enough. So he ran faster and faster, without stopping, until he finally dropped dead.

He failed to realize that if he merely stepped into the shade, his shadow would vanish, and if he sat down and stayed still, there would be no more footsteps.

There’s much to analyze about this passage, but I offer it here as a summer reminder particularly for us educators. It’s mid-July, which means the summer is almost over (I’m so sorry to have acknowledged that!), so we hunker down into the home stretch of our summer work. We still have research to do, classes to prepare, articles or books to write, projects to finish, etc. I’ve checked a lot of big projects off my list so far, but I have others that remain. They cause me to turn around and see my shadow. They cause me to be more alert to the sounds of my footsteps urging me on. They say to me,

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid. (T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”)

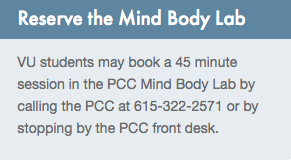

But for now, for the next few weeks, let’s all agree to remember–at least a few times–to “step into the shade” and “sit down and stay still.”

Practice

For a practice to accompany this idea, I go back to one of my favorite and most-read posts: “Stories of the Slow Professor.” It ends with a simple practice. Stop, step into the shade, sit down, and try it.