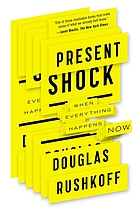

This work of mindfulness–in essence, focusing awareness on the present moment–has me noticing more clearly how I experience time. Despite the best efforts of clocks and schedules, time is a subjective, varying, and malleable  phenomenon. In October’s “Stories of the Slow Professor,” I wrote about it from the perspective of how we talk about our work. In December, I mentioned that one of my favorite recent books is Douglas Rushkoff’s Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now, in which he distinguishes between the “presentism” we chase by always being plugged in and logged on and the other “now” of experiencing the moment and place right in front of us. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how my notion of time is influenced by my discipline.

phenomenon. In October’s “Stories of the Slow Professor,” I wrote about it from the perspective of how we talk about our work. In December, I mentioned that one of my favorite recent books is Douglas Rushkoff’s Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now, in which he distinguishes between the “presentism” we chase by always being plugged in and logged on and the other “now” of experiencing the moment and place right in front of us. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how my notion of time is influenced by my discipline.

William Faulkner famously wrote in one of his novels, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Although this refers to the characters in his fictional universe whose Southern and familial pasts are constantly with them, the quote also captures something essential about the discipline of literary studies. We have our own grammar for talking about the objects of our inquiry: we use what’s called the “literary present” tense, which means that

“we consider the text, its events, and its characters alive every time we look at the page. Each time we read Hamlet, he agonizes over what to do about his father’s death; each time we read Moby-Dick, Ishmael joins Captain Ahab in search of the white whale; and each time we read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck decides that helping Jim escape slave-catchers is worth going to hell. We talk about the texts we love as offering something new with each reading.” (Chick, 2009, p. 49-50)

This sense of “an eternal present” (Vanderbilt Writing Studio) can certainly–as in the case of Faulkner’s characters–lead to the worrying, dwelling, and ruminating that mindfulness seeks to quiet. But it doesn’t have to go there.

Instead, I think of two layers of presentness in our approach. First, the text–no matter when it was published, no matter when it’s set–is always now. The action in the plot is always happening, again and again, every time we look at the page. We see these texts as “still alive, generative, and inviting of new questions, approaches, interpretations, and significance” (Chick, 2009, p. 49). Also, we readers are fully present with the text as we read, anticipating the discovery of an additional nuance in the language, the metaphorical landscape, or the characterization of the fictional people we thought we already knew so well. Paradoxically, while the world inside the text is always there, it also offers something new each time we visit it.

Instead, I think of two layers of presentness in our approach. First, the text–no matter when it was published, no matter when it’s set–is always now. The action in the plot is always happening, again and again, every time we look at the page. We see these texts as “still alive, generative, and inviting of new questions, approaches, interpretations, and significance” (Chick, 2009, p. 49). Also, we readers are fully present with the text as we read, anticipating the discovery of an additional nuance in the language, the metaphorical landscape, or the characterization of the fictional people we thought we already knew so well. Paradoxically, while the world inside the text is always there, it also offers something new each time we visit it.

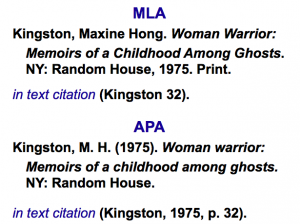

This attitude toward time is captured in how we document research. Documentation styles are painstakingly precise and, as a result, fascinatingly meaningful. In the humanities like literary studies, we use MLA citation style, which illustrates that the writer and the text itself are paramount. In our bibliographies, we list our sources by noting the author’s name, the title of the work, the location and name of the publishing company, and then the year of publication. In its most recent edition, MLA added the publication medium at the very end to distinguish digital from print sources. When citing within the body of our writings, we only use the author’s name and page numbers of specific passages. We don’t even bother with the date. Social scientists, on the other hand, foreground the date of publication in the bibliographic order: author’s name, date of publication, title, location, publisher. (There are other differences that are equally meaningful, but I’ll stay focused here on time.) Their in-text citations and even mentions of a text always include the date because when something was published determines its relevance and sometimes even its validity. For us, the date is an afterthought because the texts and the ideas within them are timeless and eternally present.

I could go on and on about the literary present (ha!), but I’ll stop here. I’m curious: how does your field represent time, and why? And how does that affect the work you do and how you see the world?

Practice

The fundamental act of a mindful practice is being in the present moment. Try this “Complete Meditation Instructions” recording from UCLA. Follow her instructions that so carefully and gently bring you and bring you back to now. She offers 10 minutes of guidance and then periods of silence. If you’re unable to sit for the whole 19 minutes, feel free to stop it when she shifts into silence.

“Complete Meditation Instructions” recording from UCLA. Follow her instructions that so carefully and gently bring you and bring you back to now. She offers 10 minutes of guidance and then periods of silence. If you’re unable to sit for the whole 19 minutes, feel free to stop it when she shifts into silence.

—

* In my editing work, I have to use APA style, so to keep me practicing this unfamiliar style, I’ve been using it in The Mindful PhD as well. I think I’ll now return to my “native” style, which reflects my worldview more precisely.

—