Last week, I attended my 10th consecutive conference of the International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (ISSOTL)–in many ways, the highlight of my academic year, as it feels very much like ‘going home.’ After five days, though, it’s good to be back in my real home, and I’m grateful for a Sunday to soothe my conference hangover. My presentations and conversations there consistently kept Faculty Careers & Work Lives (O’Meara, Terosky, & Neumann, 2008) on my mind. This book-length study focuses on the language, tone, and storylines of the ways in which we and others discuss our profession. Based on their own work plus an analysis of more than 1,000 books and articles, a thorough lit review on the research, and works written by faculty themselves over the last 20 years, the authors point out that our dominant narrative is one of “constraint” (p. 2): full of barriers, outside forces, frustration, and exhaustion, with language like “‘just making it,’ ‘treading water,’ ‘dodging bullets,’ or barely ‘staying alive'” (p. 2).

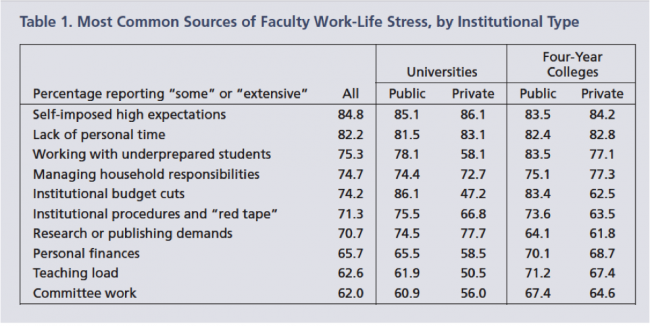

Despite its focus on our challenges, this narrative of constraint doesn’t offer much analysis of the sources of frustration, exhaustion, and stress. A recent article by Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber called “The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy” (2013) offers some insight into this lack of careful analysis or solution-seeking when it comes to faculty stress. Instead of remaining silent or merely complaining, they conclude that “Being honest about our stress may be a first step in challenging the culture of speed” (Berg & Seeger, p. 6). Why aren’t we fully honest about our stresses? They cite the “discourse of individual responsibility” (p. 6) that blames the stressed, rather than acknowledging–much less considering solutions to–the contextualized, systemic, and social factors that create it. Additionally, because non-academics cast us as “the leisured class,” we’re bound up in a “culture of guilt and overwork” (Berg & Seeber, 2013). In addition, modern political and economic threats to the university engender a “discourse of crisis” (p. 5) compelling us to act now to fix the problems facing higher education. This sense of urgency on behalf of the institution exacerbates the sense that we’re not doing enough fast enough–so our individual woes are irrelevant and selfish. (This language also affects students and their learning with its focus on efficiency, standardization, and rushed time to completion.)

Some years ago, Jordan Landry (English, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh) introduced me to this notion of the professional stories we live by and, more importantly, the power to write those stories ourselves. She said we can live the “beaver narrative” (busybusybusy, working hard all the time because there are always more trees to harvest and lodges to build) or the “otter narrative” (approaching everything with a sense of play, floating on our backs in the sun, hunting and working as necessary). This distinction isn’t really about the work we actually do as much as how we experience our work lives, or the narrative we tell ourselves and our junior and future colleagues about the quality of our lives.

Like Jordan and her “otter narrative,” O’Meara, Terosky, and Neumann point to a second story we tell about our work lives: “the narrative of growth” (p. 3). In this version, our stories revolve around our professional fulfillment, learning, agency, relationships, and commitment (p. 25-26). The authors point out that this story of potential is often overpowered, over-heard, and over-narrated by our stories of feeling constrained.*

Being aware of these narratives, their sources, their frequency, and their alternatives gives us the agency to construct our own stories (Berg & Seeber, p. 5). Once we see the varied stories and storytellers, we can learn to tell ourselves and others stories of growth and otters–not in an act of denial of the difficulties of our work lives but in an act of experiencing these difficulties differently, claiming some authority over our lives, and being open to meaningful moments of fulfillment, calm, and happiness. Taking the time for this reflection is critical: “‘If we are busy doing there is no chance to be.‘ This is as true for our students as it is for us. Time for reflection is not, then, a luxury, but crucial to effective teaching and learning” (Berg & Seeber, p. 5).

Berg and Seeber look to the goals and rhetoric of the slow food movement in analyzing and responding to these challenges. This “slow” thinking about our careers and work lives is “‘approached with care and attention–an attempt to live in the present in a meaningful, sustainable, thoughtful and pleasurable way'” by practicing “‘habits of conducting our work and our lives in ways that promote both our own and others’ well-being'” (Parkins & Craig, 2006, qtd. in Berg & Seeber, p. 6). Ultimately, this isn’t a private or selfish act but a political one that supports and even transforms our institutions by resisting the push toward efficiency and standardized outcomes: by “acting purposefully, thereby cultivating emotional and intellectual resilience” in our work lives enables us “to challenge the corporate university and maintain the values of a liberal education” (p. 5).

Practice

To take a break from the haste of doing and thinking, here’s a practice introduced to me by my mindfulness teacher-in-training colleague Eydie Cloyd (Vanderbilt School of Nursing) that will help you hit the pause button and ultimately create habits of slowness, deliberation, reflection, and agency–or mindfulness. Do it sitting at your desk, walking to your class, taking a break from grading, or sitting in a meeting. (During a bomb scare at Vanderbilt on Monday, I began my class with a group of 15 graduate students with this practice.)

- Touch the tip of your pinky finger with the tip of your thumb, and then lower your thumb to trace the inside of your pinky down to your palm. Take the time to slowly and silently count to three or even four as you travel this distance.

- Follow your thumb with your breath, breathing in as you reach your palm and out as you return to your fingertip. (Click the image to the right to see a video.)

- Focus your attention to the sensations of your fingers. Notice what thoughts arise as you slow down. As these thoughts arise, notice them, and then return your attention to your fingers and your breath.

- Now, touch the tip of your ring finger with the tip of your thumb, and then trace the inside of that finger to your palm using that same deliberate pace, the same noticing of thoughts and returning to your fingers and breath.

- Repeat with your middle finger, and then your pointer finger.

- Reverse the direction to return to your middle finger, then ring finger, then pinky.

Take this pause whenever you need it, and notice what narratives you tell and hear this week.

—

* Both of these pieces–Faculty Careers and Works Lives and “The Slow Professor”–intersect with the research on locus of control (e.g., Hiroto, 1974; Spector, 2011), or where people locate the control in their lives: if their locus is external, they perceive their lives as controlled by outside forces and circumstances. If their locus is internal, they believe they have the ability to make choices and determine their own paths. This issue of locus of control has significant implications in our classrooms. For an early summary, see Findley and Cooper (1983) or Carden, Bryant, and Moss (2004), among many others.

—