In “The Science of Inspiration” (2013), Eric Ravenscraft highlights the neuroscientific view of inspiration, epiphanies, and “‘a-ha’ moments”:

“When you make a new connection between two ideas, it’s not just a metaphor. Your brain is literally restructuring itself to accommodate new processes…. [T]he more ‘plastic’ your brain is, the more you’re able to form creative or inspirational thoughts.”

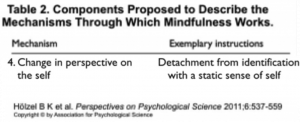

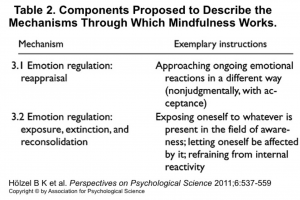

This neuroplasticity isn’t finite and has no expiration date.* Ravenscraft offers a handful of strategies for increasing neuroplasticity and nurturing inspiration, one of which is meditating. While he doesn’t get more specific, it’s important to know that a specific kind of meditation is associated with creativity and inspiration. Rather than “focused attention” meditation that…well…focuses complete attention on one thing (e.g., the breath), this type is called “open monitoring” meditation:

“the individual is open to perceive and observe any sensation or thought without focusing on a concept in the mind or a fixed item; therefore attention is flexible and unrestricted.” (Colzato, Ozturk, & Hommel, 2012, p. 1)

The greatest effects have been shown in three specific characteristics of creativity, or “divergent thinking” (p. 4): fluency (number of new ideas), flexibility (variety of new ideas), and originality (uniqueness of new ideas). So unlike some of the practices I’ve shared in earlier posts, this would be less guided, less singular, and more about…well…openly monitoring whatever is happening internally and externally at the moment.

As an Americanist,** I immediately jump to two 19th-century writers’ discussions of inspiration. “To Build a Fire” and Call of the Wild author Jack London is unsurprisingly active, proactive, even aggressive, in his image: “Don’t loaf and invite inspiration; light out after it with a club” (1903, p. 143). While his rejection of loafing and invitation hardly fits with focused-attention meditation (in fact, “invite” is a frequent word used to guide it), the spirit of his advice is to be intentional and active, one way of being mindful. Ralph Waldo Emerson‘s “Nature” (1836), on the other hand, encourages us to follow in the author’s footsteps into the woods:

Pardon my irreverence, but thanks to a graduate school seminar, this caricature of Emerson's image by cartoonist Christopher Pearse Cranch (1839) will always be a mental thumbnail for me.

“Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” (emphasis added)

Emerson’s practice is wide open, receiving, and passive–but focused on being open, actively receiving, and intentionally passive. This is open-monitoring meditation. Let’s try it.

Practice

This practice may work especially well for busy academics because we can do it anytime, anywhere, while doing just about anything. I like the simplicity and clarity of how Kenji Crosland explains it, so I’ll let his description serve as our practice this week. From his explanation, it’ll be even more obvious that, while focusing on the breath is more useful for the goal of concentration or calm attention, this kind of meditation is more conducive to creativity, new ideas, and epiphanies:

“The practice of open monitoring meditation is quite simple. In fact, I’m practicing a form of it right now as I write this blog post. As I type, I allow myself to be aware of my breathing, of my fingers touching each key, and the feeling of warmth of my back against the chair. I also am aware of random thoughts that come through my head. I observe them, and let them pass. All of this activity helps ground me in the present moment. Thus, I’m not worried about what I’m going to say or whether the words coming out on the page make sense or whether they’ll be considered ‘stupid’ or ‘brilliant’ or not. With the self-critic out of the way, the words flow effortlessly.

You can practice this meditation while doing any activity, even just walking down the street. As you walk down the street, feel your feet against your socks and shoes, and feel the pressure of the ground against your soles. Also, be aware of your breathing, and of every sight and sound. Don’t judge what you see or hear, just be aware of it. If you do judge, just be aware of the judgement, and refrain from judging that. When you do this, all thought is focused what you’re doing right now, and whatever you think you have to do, whatever email you have to answer can wait until you’re actually sitting in front of your computer with your inbox open.”

For the next week, try this practice a few times while doing various activities, and let me know how it goes.

—

* The implications of neuroplasticity for integrative learning and learning through metaphors are many, but for now, I want to explore this notion of inspiration as thinking of a new connection, a new pathway–in the mind and in the physical brain.

** In English, an Americanist is a specialist in American literature, not a xenophobe.

—

References

Crosland, Kenji. (January, 2011). Open your mind with open monitoring meditation. The Psychology of Wellbeing: Musings on the science of holistic wellness.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. (1836). Nature.

London, Jack. (1903). Getting into print. Practical Authorship, Knapp Reeve, James, Ed. NY: Editor Publishing Company. 140-143.