Brain age identification from diffusion MRI synergistically predicts neurodegenerative disease

Chenyu Gao, Michael E Kim, Karthik Ramadass, Praitayini Kanakaraj, Aravind R Krishnan, Adam M Saunders, Nancy R Newlin, Ho Hin Lee, Qi Yang, Warren D Taylor, Brian D Boyd, Lori L Beason-Held, Susan M Resnick, Lisa L Barnes, David A Bennett, Marilyn S Albert, Katherine D Van Schaik, Derek B Archer, Timothy J Hohman, Angela L Jefferson, Ivana Išgum, Daniel Moyer, Yuankai Huo, Kurt G Schilling, Lianrui Zuo, Shunxing Bao, Nazirah Mohd Khairi, Zhiyuan Li, Christos Davatzikos, Bennett A Landman. “Brain age identification from diffusion MRI synergistically predicts neurodegenerative disease”. Imaging Neuroscience 3, imag_a_00552. https://doi.org/10.1162/imag_a_00552

GitHub: https://github.com/MASILab/BRAID

Singularity: https://zenodo.org/records/15091613

Abstract

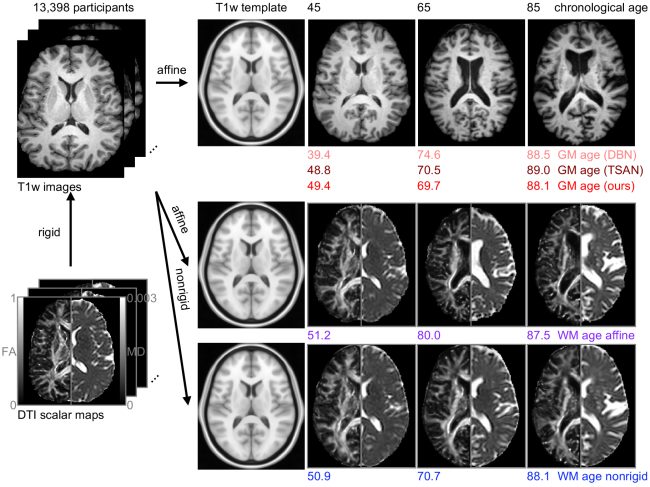

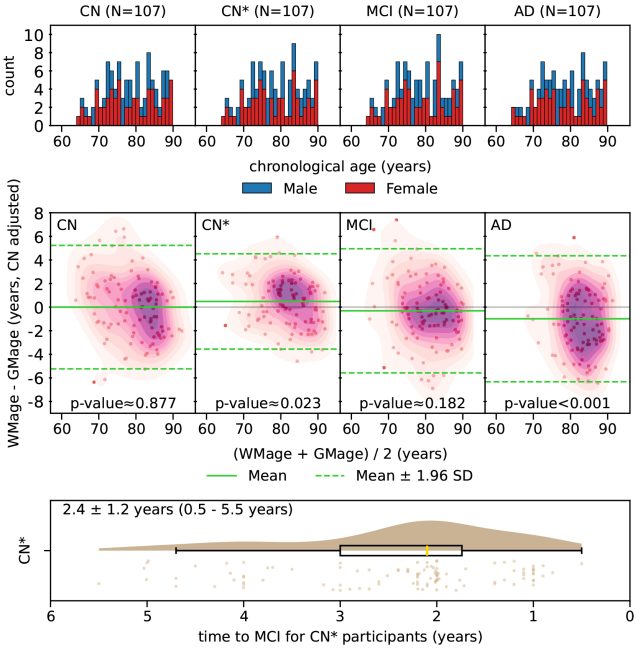

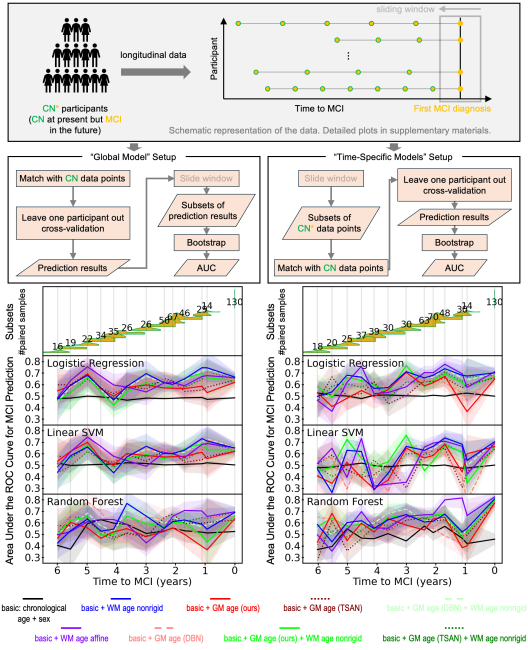

Estimated brain age from magnetic resonance image (MRI) and its deviation from chronological age can provide early insights into potential neurodegenerative diseases, supporting early detection and implementation of prevention strategies to slow disease progression and onset. Diffusion MRI (dMRI), a widely used modality for brain age estimation, presents an opportunity to build an earlier biomarker for neurodegenerative disease prediction because it captures subtle microstructural changes that precede more perceptible macrostructural changes. However, the coexistence of macro- and micro-structural information in dMRI raises the question of whether current dMRI-based brain age estimation models are leveraging the intended microstructural information or if they inadvertently rely on the macrostructural information. To develop a microstructure-specific brain age, we propose a method for brain age identification from dMRI that mitigates the model’s use of macrostructural information by non-rigidly registering all images to a standard template. Imaging data from 13,398 participants across 12 datasets were used for the training and evaluation. We compare our brain age models, trained with and without macrostructural information mitigated, with an architecturally similar T1-weighted (T1w) MRI-based brain age model and two recent, popular, openly available T1w MRI-based brain age models that primarily use macrostructural information. We observe difference between our dMRI-based brain age and T1w MRI-based brain age across stages of neurodegeneration, with dMRI-based brain age being older than T1w MRI-based brain age in participants transitioning from cognitively normal (CN) to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (p-value = 0.023), but younger in participants already diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (p-value < 0.001). Classifiers using T1w MRI-based brain ages generally outperform those using dMRI-based brain age in classifying CN versus AD participants. Conversely, dMRI-based brain age may offer advantages over T1w MRI-based brain age in predicting the transition from CN to MCI.